The Golden State’s politics beyond the blue

By LAILA AZHAR — features@theaggie.org

As soon as the clock struck 8 p.m. Pacific Standard Time (PST) on the night of the 2024 presidential election, the state of California was called for Democratic candidate Kamala Harris.

“At the top of the hour, 11 o’clock here, East NBC News can project that Kamala Harris will win in the state of California,” the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) news broadcast announced immediately following California polls closing. States including Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin — whose polls had closed hours earlier — were still considered too close to call.

This was no different in the 2020 presidential election; California polls closed, and the state’s 55 electoral college votes were instantly awarded to Democratic candidate Joe Biden. Barring abrupt and dramatic political upheaval within the next two years, this will more than likely remain true in the 2028 election.

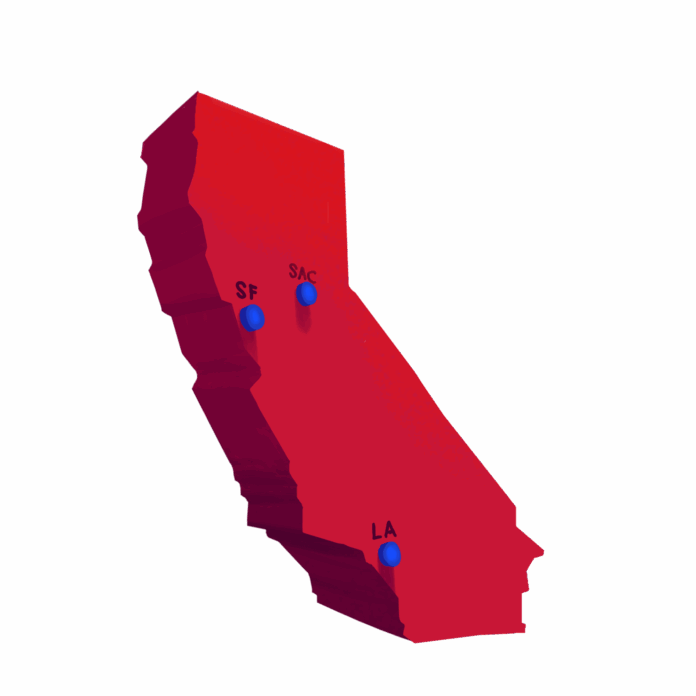

About half of California’s registered voters are Democrats, while about 25% are registered Republicans. Democrats tend to be clustered in the urban cores of the state, notably the Bay Area and Los Angeles, while much of the state’s rural areas — making up the majority of the state geographically, not population-wise — tend to vote Republican.

California is undoubtedly a Democratic stronghold. Democrats have won the state in the past nine presidential elections, likely contributing to its reputation as a staunchly left-leaning state amongst critics and supporters alike.

A 2019 Wall Street Journal op-ed described the state as “the far left coast.” Michael Shellenberger’s book “San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities” (2021) criticized the policies and leadership in major cities, including Los Angeles and the titular San Francisco.

To many, this association between California and liberal policies seems as naturally occurring as the state’s sunny weather. But, below the surface, California has a complex political landscape.

As UC Davis history Professor Kathryn Olmsted explained, the state wasn’t always viewed this way.

“I think, quite naturally, we think of California as this deep blue state, because it has been, for the last couple of decades,” Olmsted said. “But really, for a long time, until the 1960s, it was quite a conservative state. And then it sort of went back and forth. The legislature was mostly Democratic, but there were a lot of Republican governors who were very conservative.”

Olmsted is the author of “Right Out of California” (2017), a book which chronicles conservative backlash to The New Deal and labor organizing in 1930s California. This backlash, she argued, laid the groundwork for the modern conservative movement.

Appealing to anxieties about religion, gender roles and family — hallmarks of today’s conservative movement — is a strategy often thought to have emerged in the ‘70s, with the nationwide legalization of abortion. Olmsted’s book, however, traces this movement back to post-New Deal California, where leaders in local unions and communist organizations, and a socialist candidate for governor, Upton Sinclair, were described as holding radical and threatening views on gender by their opponents.

“It was hard to get, in a democracy, a lot of people to vote for you by saying, ‘We think that big businessmen should be able to do whatever they want,’” Olmsted said. “They could talk about freedom, but it didn’t get them a majority. But if they said conservatism is about freedom, and it’s also about religion, and it’s about home and it’s about traditional values, and the liberals are assaulting all of those things — it isn’t just economic issues, it’s cultural issues — they could get a lot more people in their coalition.”

Additionally, Olmsted described the process by which agribusiness leaders adopted anti-statist rhetoric.

“With the New Deal and Franklin Roosevelt, the national policy really changed,” Olmsted said. “The federal government, at first tentatively — and definitely very tentatively for farm workers — started to say, ‘Well, no, you can’t do that to your workers. They have the right to join a union, you can’t refuse to negotiate with them, you can’t beat them up if they’re on a picket line.’”

While many big businessmen had supported government intervention in the form of agricultural subsidies and breaking up strikes, New Deal policies marked a shift.

“This drew an outsized reaction from a lot of big businessmen,” Olmsted said. “They started using a lot more anti-statist rhetoric that we would recognize today as more right-wing libertarian: ‘We should have the freedom to do whatever we want, and the government is interfering with our freedom to refuse to recognize the unions.’”

Today, similar rhetoric is often used by Silicon Valley tech companies, which purport to oppose state intervention. Prominent big-tech figures such as Peter Thiel, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg are either self-described or commonly thought of as libertarians, despite the invention of the Internet being a United States government defense project.

Silicon Valley Super PACs, or independent expenditure-only political action committees, have spent millions against candidates who purportedly oppose cryptocurrency — and are gearing up to spend more in the upcoming midterm elections.

This increasing relevancy of big tech in politics has prompted some to take a more critical look at Silicon Valley technology and the policies surrounding it.

This quarter, for example, the UC Davis Feminist Research Institute has hosted a graduate seminar titled “Asking Different Questions in A.I. and Data Flows,” taught by Dr. Sarah Rebolloso McCullough.

“We’re looking at a lot of issues that don’t always make headlines,” McCullough said. “We’re looking at the resource consumption that’s necessary for their perpetuation, from rare minerals to water consumption to energy use. We’re talking about labor. A lot of people don’t know or talk about the fact that there is immense human labor that goes into training [artificial intelligence (AI)], and the vast majority of this labor is done by some of the most desperate people around the globe.”

McCullough continued by describing some of the systemic implications of AI as it continues to advance.

“Understanding AI is important because of its history [and] context,” McCullough said. “It’s really strongly steeped in [the] history of patriarchy, history of racism and militarization, of conquest, of a sort of dangerous privilege, a color blindness that actually perpetuates systems of oppression. It’s important to know that, especially if we as individuals or as communities care about creating a more just world.”

Complex Californian histories, from labor movements to the tech world, paint a multifaceted picture of the state’s politics for some UC Davis students.

“California might be a state that has a clear Democratic majority, but that doesn’t mean there’s consensus on anything,” Christina Chu, a second-year political science major, said. “Even within the party, there’s a lot of variance. Individual candidates and issues still need to be campaigned for. People’s political views are a lot more complicated than, ‘Democrats vote for anything left-leaning and Republicans vote for anything right-leaning.’”

Chu’s comments are reminiscent of the 2024 election, in which several progressive ballot measures failed to pass.

Proposition 6, which would have prohibited involuntary servitude as a criminal punishment, was rejected in California. Proposition 36, on the other hand, which restored higher penalties on certain drug and theft offenses, passed, while an increase in the state minimum wage and a repeal of limits on rent control did not pass.

“A lot of people assume that California will never pass overtly right-wing policies, so I feel like there’s almost a sense of removal from politics from a lot of liberals or progressives in California — like the other states are where the battlegrounds are,” Chu said. “But that’s not true.”

In fact, proposals similar to California’s rejected Proposition 6 policy have been adopted in “red states” including Alabama and Tennessee.

California is also not immune to actions taken by the federal government. Despite having some of the strongest abortion protections in the country, California doctors still face immense pressure from anti-abortion states. Just this month, Louisiana attempted to extradite a Bay Area doctor for prescribing abortion pills to a woman in Louisiana.

Fears about deportation and anti-immigrant sentiment disproportionately impact Californians, as the state is home to 10.9 million immigrants — more than any other state. The state also holds national importance — it hosts nearly 12% of the national population and produces nearly half of the country’s vegetables and three-quarters of its fruits and nuts. Its current governor, Gavin Newsom, appears to be gearing up to make a run for president.

California may have had a predictable role in presidential elections over the past few decades. But the state’s political history — and its present — reveal ongoing disputes over labor, technology and the policies which govern them, defying simple partisan labels.

Written by: Laila Azhar — features@theaggie.org