A hands-on experience like no other for students and faculty alike

Maker spaces exist across the country, providing a place and resources for students and teachers of all ages to participate in creating something with a perceived goal in mind. Since 2014, the Translating Engineering Advances to Medicine’s Molecular Prototyping and BioInnovation Laboratory (MPBIL) has been a maker space geared toward people interested in biology, engineering, and biotechnology. UC Davis is currently the only school in the UC system to have such a space and has inspired other schools to start their own biomaker labs.

Marc Facciotti, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the UC Davis Genome Center, has seen many students and projects come through this space.

“[A maker space] is place that has low barriers to entry for a lot of people, like technical cost barriers, to come and be creative and make stuff,” Facciotti said. “The idea [behind the biomaker lab] is that we want to provide a place for people to come and make things in biology — engineering biology itself or engineering things for biology.”

The process begins with a specific problem or end goal that the student wants to achieve, but, aside from knowing that detail from the start, the possibilities are endless.

“Basically, what we do is we have genes that we’re interested in into e. coli, and e. coli can make proteins using that genetic information,” said Lisa Illés, a third-year biological systems engineering major. “Those proteins can be super useful. We could make vegan cheese, for example, by putting cow’s proteins into some e. coli.”

Though the biomaker lab has yet to see a large number of students, Facciotti states that the interest is growing and that they’re hoping to have more success cases to show that undergraduates can excel with independent projects, when given the time, space and resources.

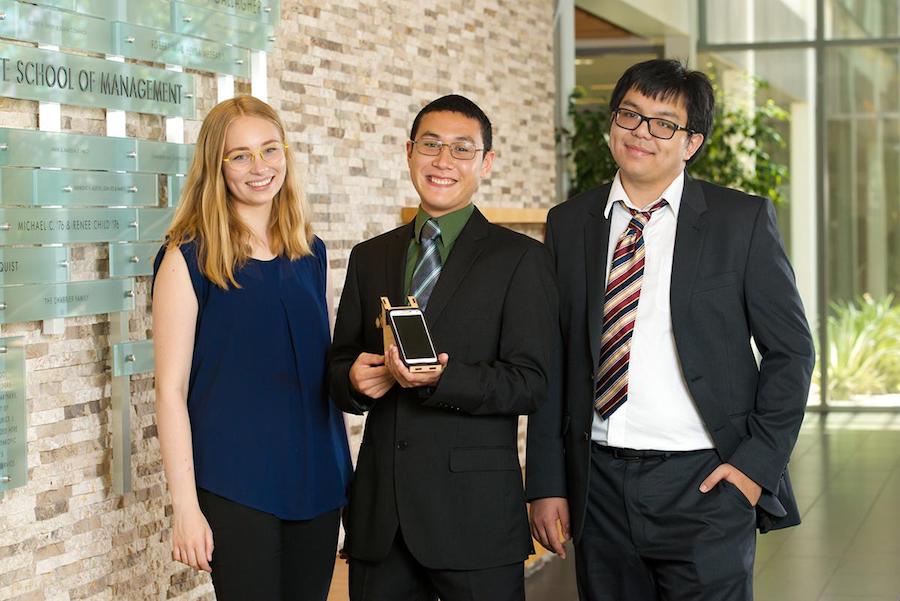

Of the most recent of three projects to come out of the lab — Chromatiscope, founded by Nicholas Dao and Alexander Godbout — became its own company. Illés and others have pitched in throughout the past two years. The Chromatiscope is a simple device for high school labs that combines four common pieces of laboratory equipment: a microscope, spectrophotometer, colorimeter and fluorimeter. It is is a cost-efficient tool, due to the use of computer code and the fact that most, if not all, students have smartphones, meaning that there’s no need to add machinery for computing power. After acquiring information through labs, students can check their results from the Chromatiscope on the accompanying website.

Some of Chromatiscope’s prototypes were funded by VentureWell, which has backed other projects from the MPBIL, such as Ravata Solutions and Ambercycle. Chromatiscope also won second place in the Big Bang Business Competition earlier this year.

“It came out of a course that we offered in that facility,” Facciotti said. “We were doing a training exercise, and it involved making new pieces of DNA that would make e. coli light up different colors. It was a relatively simple thing, and it wasn’t the main point of the quarter, but it was linked with trying to build a kit for a high school teacher.”

Due to new California education standards, local schools including Davis High School have been changing their curriculum to meet the hands-on portion of science classes. However, the outdated equipment and lack of funds causes problems, because replacements would cost thousands of dollars.

“[Ann Moriarty] told the class, ‘Could you build us this new device [the Chromatiscope] to replace our existing device which doesn’t work very well anymore?’” said Nicholas Dao, one of the founders of Chromatiscope, who received a bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering. “Me and my cofounder, Alexander Godbout, decided to take it on, and we started using the lab space simply because it was available to begin development. That’s largely where we founded our company out of.”

Davis High School is slated to receive the Chromatiscopes within the next few weeks. Dao stated that, if the Davis High School version goes smoothly, he and Godbout will pitch the idea to more California high schools.

“You go out into the world, identify a problem and build your solution to that problem around the people who need that solution and the problem itself,” Illés said. “I think that the fact that Chromatiscope did that made it a super valuable product. Even if it’s not going to be mass-produced, it still has value to the people who have used it because it solves an urgent need for them.”

That problem-solving aspect is an important aspect of the MPBIL, and Facciotti hopes that the biomaker lab can provide students an opportunity to try something new without the fear of failure.

“The experiment ‘worked’ or this thing ‘worked’ or ‘didn’t work’,” Facciotti said. “ ‘The experiment yielded something that was unexpected. So it didn’t work.’ That’s the wrong attitude, so you have to fight this. No, it gave you some information that you now have to interpret and you do it again, or you revise what your hypothesis was. This idea that everything has to ‘have a definite outcome’ or ‘have a predetermined outcome’ is something I find that I have to fight against. Science is not measured that way. Neither is engineering.”

Facciotti hopes that UC Davis will work harder in creating and promoting opportunities for undergraduates to get involved in MPBIL and other maker spaces early in their college careers.

“We’ve got 30,000 students, who, in many cases, come with the mindset that their job is to consume something and then wait four years to get their piece of paper at the end,” Facciotti said. “I would like the mindset and the structure to be something where we are encouraging more creative activities.”

Both Illés and Dao have experienced these difficulties as undergraduates and hope that UC Davis will continue to support these types of extracurricular activities.

“I really do think that a lot of people have good ideas, but the problem is that you don’t know the resources that are available,” Dao said. “You can have a good idea that really could be marketable, if you had the right resources to guide and direct you, but the unfortunate reality of UC Davis is, and they’re aware of it too, [that the resources are] still not very well publicized.”

However, Illés also thinks that the expectation of college lasting only four years and the stigma around students taking “extra” years are key parts of the problem.

“More people should show up to these spaces,” Illés said. “If that means making time in your schedule by taking a fifth year, I think more people should do that. Especially engineers. The best thing you can do during your time here is make something.”

Written by: Jack Carrillo Concordia — science@theaggie.org