Living in an environment that perpetuates homophobia and gender inequality, Courtney Caviness had to hide her identity in fear of retaliation, until she decided to leave

By LEVI GOLDSTEIN — features@theaggie.org

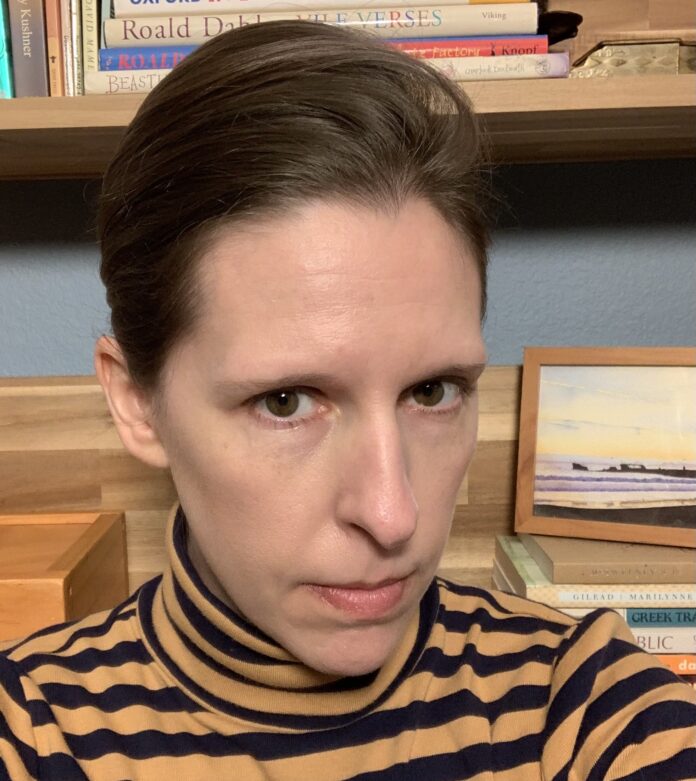

Courtney Caviness, a lecturer of sociology at the University of California, Davis, has a commanding presence in the classroom. For each word she speaks, each syllable is distinctly pronounced. Her firm, authoritative voice projects across the rows of students.

“I hate the military,” Caviness said.

She is also a veteran.

Caviness joined the intelligence branch of the United States Army in 2006. After obtaining her bachelor’s degree in English at the University of Iowa, Caviness was feeling directionless. She was indecisive about what she wanted to get a degree in and had changed majors a few times.

“I’m a serial dabbler,” Caviness said. “I like to know something about almost everything.”

Additionally, she had navigated multiple unhealthy relationships that left her with a shaky sense of self.

“I was in a place in my life where I really needed to do something drastic, to change my geographic location and disrupt all facets of my life, just have a big change,” Caviness said.

For her, this change was joining the military. It was exactly the kind of challenge she needed to push her forward.

It was also an opportunity to escape the Midwest, where she said she never fit in. Caviness explained growing up feeling like an outcast because she presented in a more masculine manner than her peers. Still today, she wears button-up shirts with the sleeves rolled up that stay tucked in during her work days and a pair of neutral-toned dress pants.

“I’ve always been, in terms of gender, someone who didn’t fit the traditions of what a girl or a woman is, in relation to those expectations or my appearance or any of that,” Caviness said. “I had no desire to do hair or nails or play […] those hand-slapping games.”

But the army didn’t feel like home to her, either. Caviness said she felt like the odd one out from the beginning.

“I had a reputation, jokingly, from one of my basic training drill sergeants […] for being the person who thought differently and who didn’t politically align; that’s for sure,” Caviness said.

Caviness was already enlisted when she began coming to terms with her sexuality.

“It was confusing and isolating, especially being in the military and knowing as I was working through it that there was this added layer of needing to keep some level of secrecy, […] that [it] could potentially be used against me or could be aired,” Caviness said.

Caviness’s fears were not unfounded. 2006 was five years before “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed.

The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, implemented in 1994 by the Clinton administration, allowed gay, lesbian and bisexual citizens to serve in the military as long as they did not disclose their sexuality. This meant that if the military were to find out that Caviness was not heterosexual, she could potentially be dishonorably discharged, which would result in a complete loss of veterans’ benefits, according to TIME Magazine.

The justification for the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” bill was that LGBTQ+ persons in the military “create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability.”

In an article published in the Journal of Homosexuality in 1995, Dana Britton and Christine Williams, sociology professors at the University of Texas at Austin, explained that heterosexuality, masculinity and misogynistic conduct are emphasized in the military in order to encourage and preserve strong bonds among male soldiers, which is thought to be central to an army’s success in armed conflict.

LGBTQ+ members of the army are believed to threaten that, according to Britton and Williams. Thus, the military actively discourages homosexuality through bans on service like “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and, according to Britton and Williams, the use of force and discipline.

Caviness said she experienced a culture of “hegemonic masculinity” during her time in the military, one that perpetuates gender inequality and reinforces men’s dominant position in society. She also identified the sense of unity characteristic of military life.

“There’s certainly a lot of emphasis placed on camaraderie and building those relationships and supporting one another and having some level of loyalty,” Caviness said.

Caviness was able to form strong friendships with other service members.

“Having some level of bonding with people that I was in that situation with became a very important thing,” Caviness said. “I think it’s easy to connect with people when you’re all in the same situation where you don’t have outside influences and you can’t get away.”

Despite this, Caviness often felt isolated. Her queer identity made her an outlier and a direct challenger to the military’s homogenous culture, which meant that she could potentially be targeted.

“The people that I knew, myself included, just had a sense that it was possible or had this looming cloud,” Caviness said. “So we would do our best to sort of manage information about ourselves or manage what we said about various activities to help avoid any potential [incident].”

Caviness said her experience differs from many other LGBTQ+ members of the army. She rarely encountered blatant homophobia. Caviness acknowledged that her privilege may have contributed to her feeling safer than others in the same situation.

“I had identity categories and attributes about myself that I think were more palatable to the military, that were less threatening,” Caviness said. “I think being a white woman who is cisgender sort of fits into the military mold in terms of appearance and demeanor and ability to adhere to or conform to its standards. That made me sort of an ideal worker in some ways for the military.”

Despite this, the stress of having to hide a part of herself and of having to keep a relationship a secret eventually led her to the decision to disclose her sexuality to the military.

“It felt like not just a burden to me; […] it felt like I was also putting [my partner] through that situation as well,” Caviness said. “My sense was that I couldn’t really do the sorting out in terms of identity that I needed to do in the confines of the military — in terms of mental health, for example.”

But the process for being discharged was not an easy one. Caviness had to first answer a series of questions in front of military leadership. She said they were looking for proof that she was telling the truth about her sexual orientation. But she was careful to give very few details.

“I had done enough research to know that disclosing certain specifics would be more likely to […] grant me a dishonorable discharge or something other than honorable,” Caviness said. “I refused to answer those questions because that felt really invasive and could be used against me.”

Caviness said she was told the military would be ignoring her claims and would allow her to continue to serve, which she wasn’t willing to accept.

“I continued to push the issue. I wrote a letter to the commander and said, ‘I understand that you choose not to discharge me on this basis, which is fine, but you will know that I will serve openly.’”

After this, the military moved forward with her discharge. But Caviness said she faced retaliation because of her coming out. She was put on two 24-hour security shifts in a row when it would normally be on rotation, and she said she wondered if that was intentional. She also, for the first time, experienced an act of violence, which she said she suspects came from a place of hate or homophobia.

“After I had disclosed to the military and my separation had begun or was in the works, I was living in the barracks, and my car was vandalized,” Caviness said. “It was bashed with a blunt object and there was something sprayed all along the side. […] Maybe soda or something? But it was like this sticky mess all over the side of the car.”

When “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed, Caviness said she felt relieved that others would not have to experience the same challenges that she did. But unfortunately, despite LGBTQ+ members of the military being able to openly serve, the culture that creates a hostile environment for them still remains. For example, in a New York Times article, Necko Fanning describes receiving death threats from and being called slurs by fellow service members shortly after coming out.

Moreover, it is still possible for policies restricting military service for LGBTQ+ people to be implemented. In 2019, Trump instated a ban prohibiting transgender people from enlisting, according to NBC News. The policy is no longer in effect as of 2021.

It was only after Caviness left the military that she was able to be fully herself. She recalled a sense of freedom and relief because she no longer felt the constant anxiety that was part of her military experience.

After Caviness completed her master’s degree at Texas State University, her partner at the time, to whom she is now married, helped her move to California to complete her Ph.D. at UC Davis.

“We drove my little hatchback from Texas to California almost straight through,” Caviness said. “I think it took two days, and we had two cats in the back. That was wild.”

Caviness went on to become a lecturer at UC Davis. In her classes, Caviness shares a message of hope with her students.

“You don’t have to have it figured out,” Caviness said. “Things will not necessarily get easier […] but everything is temporary. And there does seem to be some sort of light at the end of the tunnel in a way, even though it doesn’t seem like it. And one day you’ll care so much less about what other people think, and it’s the most freeing feeling.”

Written by: Levi Goldstein — features@theaggie.org