It’s self-defeating and disadvantageous — but we still count on it every time

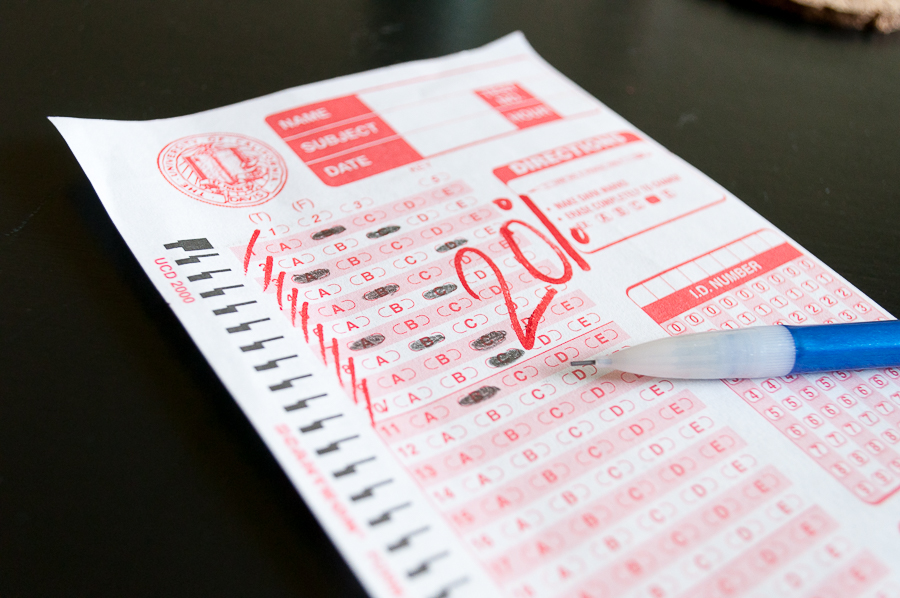

It’s midterms week and grade curving is at the forefront of many students’ minds. It’s common after a difficult exam to hear the sigh of a spent student and their silent (or maybe noisy) plea to the grade gods: “I hope there’s a fat curve on that one.” Since coming to college, I’ve learned that some things aren’t to be questioned — and if one is on the good side of the arbitrary mathematical equation that determines pass and fail, the mouth is best kept shut.

It’s midterms week and grade curving is at the forefront of many students’ minds. It’s common after a difficult exam to hear the sigh of a spent student and their silent (or maybe noisy) plea to the grade gods: “I hope there’s a fat curve on that one.” Since coming to college, I’ve learned that some things aren’t to be questioned — and if one is on the good side of the arbitrary mathematical equation that determines pass and fail, the mouth is best kept shut.

But there’s a certain ridiculousness to grade curving that must be addressed. In our daily lives, we evaluate things at face value. Let’s say we go to Trader Joe’s to buy some strawberries for our morning oatmeal. In most of the cartons, 50 percent of the strawberries are rotten. In some of the cartons, close to 70 percent are moldy and inedible. As hungry students, we don’t decide to buy the strawberries that are half-spoiled; we choose not to buy them at all. But apparently, when this analogy is transferred to academics, it suddenly makes sense that the standard of the average is the standard overall. Grade-curving is self-defeating at best — and downright disadvantageous at worst.

It’s the students who lose at the end of the day. To future institutions of study as well as employers, it appears that we know much more than we do. Our consolation is that no one appears to know as much as they know. That’s not a really great way to go about life. This dilemma is even more pronounced to students who enter the workforce immediately and must recall skills and concepts from their degrees.

And while most of us are quite thankful to see our grades rise, it’s not without some internal conflict. Students are sincere by nature, and it bothers them when they do poorly — even if their grades are adjusted at the end of the term.

“You begin to feel very conflicted about your accomplishments in the classroom,” said Neha Pullabhotla, a second-year computer science major. “Part of you stops and evaluates if you deserve to pass, while the other part insists that you’ve worked very hard and deserve not to fail.”

Pullabhotla brings up a good point: Students now have the added mental stress of deciding whether they warrant the grades they get. It used to be the numbers that said it all. We aren’t defined by our grades, but they are good indications of mastery and progress.

No one is implying that grade curves be abolished. I for one have benefited many a time from them and would be sad to see them go. Instead, there needs to be a reevaluation from the two parties who issue grades — students as well as the professors and TAs who instruct them. The teaching staff must write realistic forms of assessment, and students must be willing to be challenged in ways they haven’t been before. If tests aren’t doable, professors lose out on opportunities to reemphasize important concepts. Students lose interest, and as a system we aren’t able to fill the gaps that are created.

I’ll employ another analogy to illustrate this point. If students are just learning their ABCs, the form of assessment shouldn’t be participation at the Scripps National Spelling Bee, but rather spelling out some words that are a level or two higher than what they’ve interacted with before. In exchange, students should be willing to think about information in a different and critical way — maybe even for the first time on an exam. A middle ground exists, but at present neither party seems to want to give in.

My fear is that students are settling for less in this current system. There isn’t really a chance to raise the bar higher and push the envelope when the prevailing attitude is that one only needs to be better than the peer next to them. That’s a despicably low and overall lazy standard. The goal of education is to learn and be curious. And students craning their necks to see if their score is better than their neighbor’s isn’t the type of curiosity I’m referring to.

Written by: Samvardhini Sridharan — smsridharan@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.