How it uses apophenia and liminal space to create a “fear of the dark”

By CORALIE LOON — arts@theaggie.org

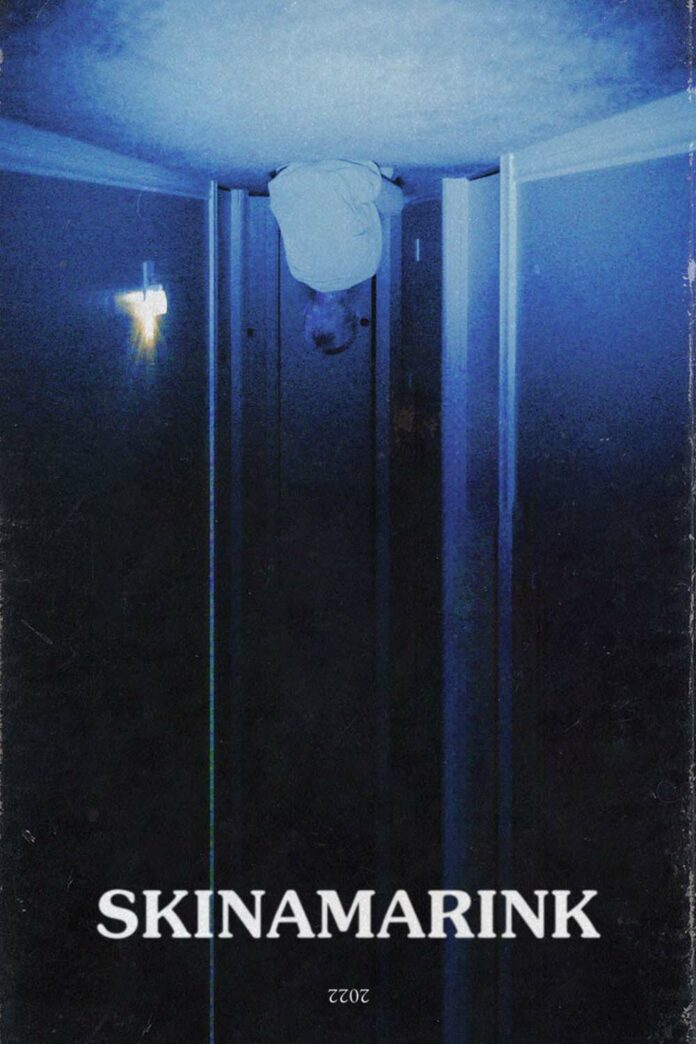

You may be surprised to learn that one of the “scariest films ever made” cost only $15,000 to produce, according to Independent. The indie horror film “Skinamarink,” which was released in theaters in January and is now streaming on Shudder, has received rave reviews and a flurry of conflicting viewer feedback for its unique and unsettling depiction of childhood fears. Whether responses to the film are positive or negative, “Skinamarink” has successfully made an impact despite its low production value. In fact, it may be the film’s visual simplicity, grainy film quality and lack of linear structure that make it so impactful.

“Skinamarink,” directed by Kyle Edward Ball, follows two young siblings, Kaylee and Paul, who wake up in the night to find that their father is gone. The rest of the film is a slow-paced, ominous unfolding of every child’s worst nightmare: being left alone in a dark house. This fear of the familiar becoming unfamiliar, of the home becoming a twisted distortion of itself, is manifested in the viewer not through a flashy plot but through prolonged stillness and silence.

In between zoomed-in shots of Kaylee and Paul huddling together on the couch or passing between rooms, much of the film is composed of long shots of dim hallways, staircases and empty spaces. In these moments of darkness, oftentimes the only visual movement is the speckled and constantly shifting film grain, which undulates with all the meaning of a low-lit home video.

By giving us something other than just stillness, and something more than just darkness, these shots reproduce a nightmarish, childlike imagination in which shapes in the dark develop their own meaning. This effect is often referred to as apophenia, which Merriam-Webster defines as “the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things” — essentially, to see things that aren’t there.

“Skinamarink” creates apophenia not only through visual techniques but also through sound. The silence in between the children’s anxious and barely decipherable whispers is more than just silence; it’s fuzzy white noise, a cheap microphone’s best attempt at capturing the subtle frequencies and air currents in a quiet room. Like a child staring into the dark corners of their bedroom, the viewer can’t help but pick patterns from the grain and fuzz, seeing or hearing things that don’t exist.

The film’s reliance on atmosphere and prolonged silence in lieu of action or a cohesive plot has not gone without criticism. Despite having a 71% on Rotten Tomatoes and a mostly positive Critics Consensus, the audience score sits at just 44%, with just as many viewers finding it terrifying as “frighteningly dull.”

It seems almost impossible that a film some claim to be one of the scariest of all time is also one that has bored so many to death. Yet, the expertise of “Skinamarink” lies precisely in its nonconformity and its refusal to exist in one space or another. It’s both mundane and terrifying, motionless and full of imagination, existing and making use of a type of liminal space.

“Liminal space” broadly refers to a transition or a threshold between things, whether conceptual or concrete. However, The Atlantic explains how the term has been popularized as a way to describe physical spaces that are often “devoid of humans and, in some cases, distinctly surreal.” Images of places such as abandoned shopping malls or long, empty hallways take up liminal space because of their unique combination of a familiar or recognizable place with “unnatural emptiness.”

Aesthetics Wiki, a subsection of Fandom Wiki, describes liminal spaces as feeling “frozen and slightly unsettling, but also familiar to our minds,” combining feelings of nostalgia with unexpected discomfort and eeriness.

Liminal space is possibly the best lens through which to understand the power of “Skinamarink.” The film uses shots of colorful Legos strewn on the floor and cartoons softly playing on the living room TV to disorient the viewer and strip them of their comfort. The toys are motionless, lying in a dark and empty room. The TV plays the same clip over and over again and no one watches it. Hallways that have been walked down a thousand times are suddenly empty, dark or even physically turned upside down.

“Skinamarink” is also a reconstruction of childhood. For the overly nostalgic viewer, it is a reminder of how our early memories are often more fantasy than reality. While we usually think of childhood as a time of familiarity and comfort, “Skinamarink” reminds us of its liminality, the discomfort of having to make sense of a world full of unknowns and uncertainties. Childhood as a lived experience is far from comforting; rather, it’s a time when the desire for comfort is so overwhelming that it will inevitably be unmet.

Perhaps those who failed to be swayed by the film’s unsettling atmosphere have outgrown such childish fears. But for the rest of us, “Skinamarink” is a harsh inversion of nostalgia, turning the vision of childhood as a place of familiarity on its head.

Written by: Coralie Loon — arts@theaggie.org