The new research may pave the way toward mass production of quantum devices

By EKATERINA MEDVEDEVA— science@theaggie.org

It is quite hard to break down something fundamental with a single atom, let alone with a subatomic particle. However, classical mechanics is an exception.

On very small scales, it is the laws of quantum mechanics that dictate properties and behavior of particles. Unique features that they outline, such as state of superposition and quantum entanglement, give rise to many applications, including the field of quantum information processing (QIP). The technologies that implement QIP can enable humanity to solve problems unconquerable for modern computing tools.

The devices of interest for these tasks are nanophotonic devices, which are able to manipulate light — more precisely, photons — at nanoscales. However, fabrication of this type of hardware that can harness quantum phenomena and eventually integrate the QIP protocols is extremely challenging, and on top of that, it needs to be affordable and scalable.

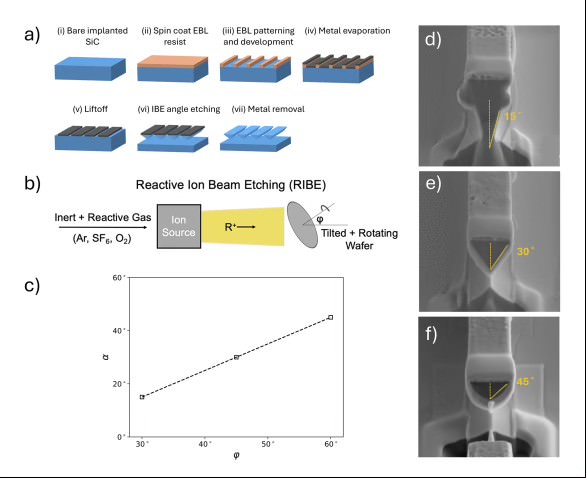

UC Davis research group, led by Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Marina Radulaski, addressed this complex of problems by proposing in their study a new method of etching the nanostructures at an angle in silicon carbide (SiC) on wafer-scale substrates. These are thin slices of SiC that can be implemented into a device.

“It is new to our field for silicon carbide quantum photonics, because what it brings is two things that have been challenging: one, the process does not destroy color centers, which are important for quantum performance, and two, with this tool we can make wafer-scale substrates,” Radulaski said. “So rather than having very small millimeter scale [chips], here we can have several inches of wafer substrate that can be bought commercially and that will enable us to either make many identical devices and deploy them to different parts — say different nodes of quantum interest — or make very complex quantum circuits on the same material.”

The mentioned color centers, also known as nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers, are small defects in the SiC substrate where silicon and carbon pairs are substituted by a nitrogen atom and a vacancy spot. These NV centers then act as quasi atoms that emit photons, which are then processed inside the nanophotonic devices.

The production of these devices consists of three main phases: generation of NV centers in the SiC substrate, design and production of photonic patterns on a metal layer and the etching of the patterns on the substrate.

“We first model these devices, which involves solving equations of light evolution in different materials and getting an idea what shape we want to make this device into,” Radulaski said. “Then we do electron beam lithography where we deposit the [electron beam resist polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)] mask [onto the SiC substrate] and bombard it with an electron gun, [located in Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory], which basically writes the shape that we want to etch. After that, we deposit the nickel mask and [perform lift-off] to transfer that shape into the metal.”

Once the patterns are created, the substrate and the mask are placed into a machine, called an etcher, that “engraves” triangular cross-section devices into the substrate.

“The specific one we have here at UC Davis is very rare and is called an ion beam etcher,” Radulaski said. “It allows us to accelerate ions to bombard this [wafer] with the metal mask [on], removing a part of silicon carbide that is not covered. And what is specific to our method, is that we tilt the wafer at an angle to direct the ions underneath the mask, and what we get in the end are these nanostructures with triangular cross-section.”

The study’s first author, Sridhar Majety, who received his Ph.D. in quantum nanophotonics from UC Davis in 2024, won the electrical and computer engineering department’s Richard and Joy Dorf Graduate Student Award for this work. This award recognizes “outstanding academic achievement and exceptional personal leadership,” according to its webpage. Furthermore, another co-author and current graduate UC Davis student, Pranta Saha, won a poster prize award for a demonstration of the team’s findings.

“Now we need to design photonic devices implementing this method and ensure that they operate well,” Radulaski said. “The light that is emitted by the color centers should enter the optical mode of the device and enter the QIP process efficiently so that we don’t lose those photons to the environment.”

There are many potential devices that can be manufactured with this method, including those used for quantum computing, quantum networking, quantum simulation and quantum sensing.

“Right now, we are also working on hybrid integration of silicon carbide nanodevices with superconducting nanowire systems that can be used as detectors for single photons,” Radulaski said. “These detectors are highly sensitive and complicated because you’re trying to detect just one particle of light, and so the systems that can do that require low temperatures and [need] to operate in a superconducting regime. We have done preliminary studies in collaboration with the Munich Technical University where we were able to deposit this superconducting material on top of our silicon carbide substrate. And now the next step is to fabricate detectors out of it.”

Written by: Ekaterina Medvedeva — science@theaggie.org