It’s all conjecture, really

By ABHINAYA KASAGANI— akasagani@ucdavis.edu

One of my dearest friends loves to use the phrase “it’s all conjecture,” which always strikes me as a little amusing. Although she is right that many things in life are based on speculation, I believe many things to also undoubtedly be true. In our society, this is simply how we have been taught to approach most things — with the understanding that there are some questions that are meant to be debated long before an answer is found.

My friend and I were sitting together when I brought up the 2015 viral dress, wondering when people decided that their interpretation was right and everyone else with an alternate opinion was wrong. When did it all stop being up for debate?

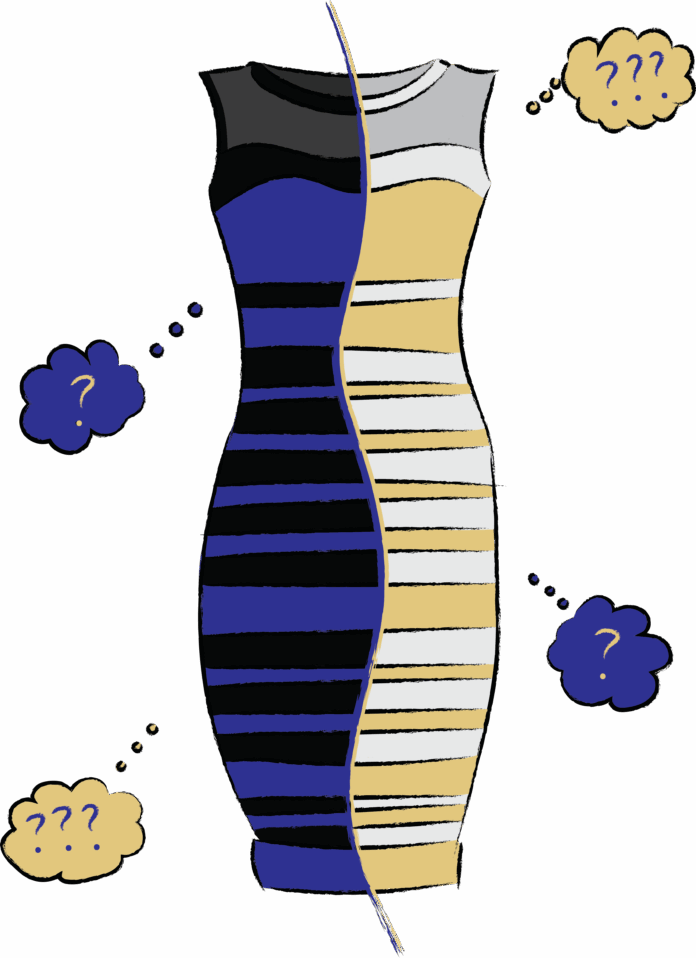

“The dress,” as it is infamously referred to, caused widespread disagreement online about whether the garment was black and blue or white and gold. The dress soared to popularity in February 2015, when Cecilia Bleasdale, the mother of bride-to-be, Grace, photographed a dress she had intended to wear to the wedding and sent it to her daughter, who assumed it was white with gold lace. Grace posted the image to Facebook, where her friends began to disagree about its color.

A few days later, the image was reposted on Tumblr, where it sparked controversy and puzzled those who could not see the dress both ways. To this day, it remains remarkable that millions of internet users found themselves unable to resign their answer once learning the truth. The digital age has done wonders for our longstanding relationship to perception, bias and truth.

What makes “the dress” such an unsettling debate is not that it caused disagreement, but that those who participated remained absolutely certain that they were right and convinced that they possessed the truth.

The reason for this dissonance was revealed several years later in a 2017 study, which theorized that these visual differences were determined by the lighting the viewer had interpreted the dress as being under — if they believed the image was taken in daylight, they assumed the fabric was white and gold; if they thought it was taken under artificial lighting, they assumed it was black and blue. Despite knowing that our perception is a result of the way in which we interact with and perceive the world, the viewers’ perspectives were limited by the absence of context, since the image could only be accessed digitally. Facts alone were not strong enough to convince them of the truth.

This is similar to how information operates online today — what is true is often more about what “feels right” and less about what really is. Misinformation flourishes on the Internet because people choose to remain and continue to be uninformed, just as they did when they learned the true color of the dress. Most people are uninterested in perspectives that contradict their own, and so choose to ignore any external criticisms and critiques they might receive.

Some people remain biased simply because they are told to — social priming, in this way, influences perception and embraces conformity, siding with the general consensus. Something as trivial as a dress worn to a wedding stands in for large patterns of polarization, whether political, conspiratorial or theoretical. “The dress” is no longer about color perception, but about the extent to which our brains selectively filter out the world, making perception passive, not participatory.

When I brought this up to my friend, she claimed that the world is no longer able to hold grief and joy at the same time and that society has grown fixated on binaries that are answerable, where one can win or best another. Ultimately, “the dress” is a Rorschach test of sorts for the digital age, wherein this bias is a feature of human cognition that is leveraged by digital platforms to produce a sense of illusion.

In actuality, it doesn’t matter whether the dress is black and blue or white and gold (the dress had been spotted at the wedding and it is, unfortunately, black and blue), but rather what matters is the understanding that things are not always as they seem. It doesn’t matter whether you’re right or wrong. The question being asked is how open you would be to considering that you might be at fault, or whether your judgment was actually a misrepresentation on your part. So, perhaps it really is “all conjecture” at the end of the day.

Written by: Abhinaya Kasagani— akasagani@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the

columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.