My experiences and core beliefs affect my views on hate speech

“Hate speech” is a term that’s used often on this campus and at universities across the country. Before coming to UC Davis, I had never heard of the term “hate speech.” It’s not like I hadn’t witnessed or faced racial abuse before; I just didn’t expect universities to have expansive speech codes that included racist language as part of the definition of hate speech.

“Hate speech” is a term that’s used often on this campus and at universities across the country. Before coming to UC Davis, I had never heard of the term “hate speech.” It’s not like I hadn’t witnessed or faced racial abuse before; I just didn’t expect universities to have expansive speech codes that included racist language as part of the definition of hate speech.

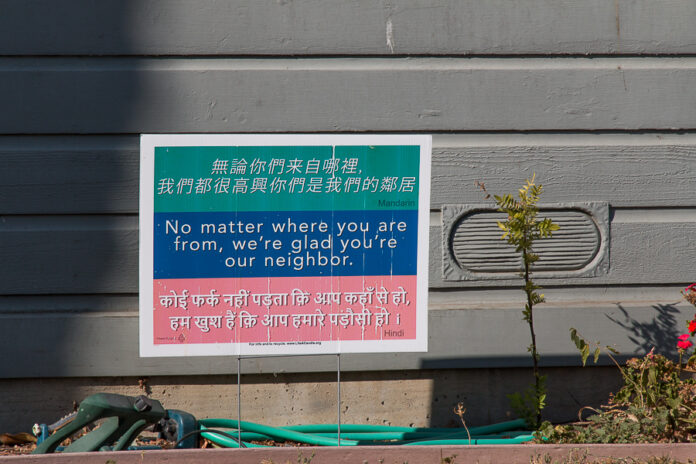

My past experiences with racial abuse had contributed to my initial understanding of hateful incidents. I’m thankful to have not faced many of these incidents, but I have witnessed many friends and strangers in such unfortunate situations. A classmate of mine was called “Ling Ling” by those who didn’t care to learn her name and wanted to make fun of her for being a recent immigrant who spoke little English. Classmates have also asked me on several occasions to say something in Chinese with the intention of repeating it mockingly. These anecdotes heightened my hatred of racism, but at the time, I didn’t see how there could be much done to stop my peers from spouting abuse.

My opinion on hate speech and its restrictions have largely been influenced by what has happened in the last few years. Ever since I first learned about the First Amendment and the Supreme Court’s considerably wide range of allowable speech, I’ve been rather open to almost all forms of speech. My perspective has been reinforced by events that have unfolded on many campuses — not just ours — where many forms of speech are viewed in violation of campus policies and either forbidden or highly impeded by protesters. Upon reading our university’s policies, you’ll find that the school offers a basic commitment to the merits of free speech. But university policy also recommends reporting hateful or biased speech that may violate the university’s speech codes.

I feel that the weight of my school experiences has made it harder for me to be critical of hate speech restrictions. These codes play a crucial role in attempting to prevent the incidents I’ve experienced from happening to other people. The issue is with the subjective nature of these rules, which depends on perspective. These speech codes can attain more legitimacy if universities set out their definitions properly for what hate speech actually is rather than giving vague examples. This will set a standard for each case to prove beyond a doubt that there’s hate involved in a given incident.

UC Davis has tried to find a compromise on this subject. The school has affirmed its commitment to free expression while reserving the right to review hate speech cases for bias. This may lead to a confrontation in the future: the guarantee of free expression may end up lacking dedication, or the restrictions on hate speech may not be as broad as proponents want them to be. It could really go either way.

Our perspectives on this issue may change as we talk to people of different backgrounds, especially since this is an ongoing issue that never seems to go away. Personal experiences have a strong impact on how we feel about political topics. If I had had different experiences, then the arguments presented here would likely be different. Hopefully there’s some form of compromise between the many different perspectives that will balance the good that would come from setting a limit on hate speech restrictions and define plainly and definitively the steps necessary to prove bigotry in hate speech cases.

Written by: Justin Chau — jtchau@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.