Best’s story

Imagine running into a wall at full speed. Now imagine doing that 30 more times. Welcome to a week in the life of a typical running back like former Cal player Jahvid Best.

While that doesn’t sound like fun, Best’s story gets worse. In a Sept. 5, 2009 game against the Maryland Terrapins, Best took a pass and tried to do what he did best: blaze past defenders with his incredible speed. However, Terrapin player Kevin Barnes had a different idea. The 190 lb. defensive back launched himself at Best, hitting him so hard that Best was sent flying. When Best landed, he rolled over and vomited on the field.

Best, being the competitor that he is, still had the desire to play football after his injury. However, luck was clearly not on his side. Only a few weeks later, in a game against Arizona State, Best, in an attempt to get into the endzone, flung his body toward the goal line. Unfortunately for him, he collided with an opposing defender. The contact sent Best sprawling into the air, high above the other players, until he finally landed on the back of his head. Right on impact, Best’s helmet flew off of his head and he looked to be in agony.

Thirteen minutes later, Best was strapped onto a cart en route to the Highland General Hospital in Oakland, where he was diagnosed with a concussion. This concussion happened to be his third concussion of the season.

Best found the courage to continue playing after the traumatic incident and eventually made it big time: the Detroit Lions drafted him in the 2010 NFL Draft. However, his story does not end happily ever after — Best’s career was eventually derailed because of successive concussions, leading to the Lions cutting Best from their team and his eventual early retirement.

Best’s story is only one of the many which have been discussed recently, as the spotlight has shone more brightly on the realm of concussions and their eventual consequences. Luckily, Best has shown no severe repercussions from his injuries as of now. However, many people are not as lucky as him and have suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), which has been linked to repeated concussions.

CTE’s societal progression

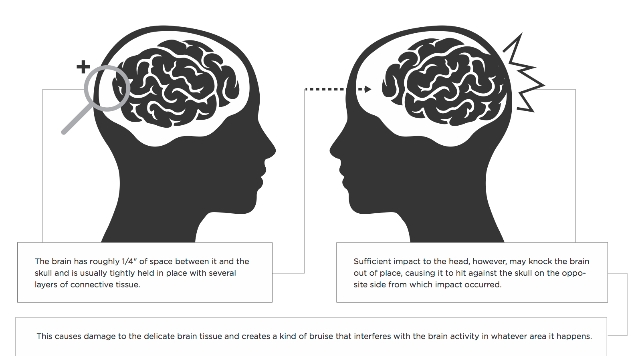

CTE is a progressive, degenerative brain disease made famous by the athletes who have fallen victim to it. CTE is found in people who have histories of repetitive brain trauma. The most common triggers are concussive blows to the head and repeated subconcussive head hits. Subconcussive hits occur when the brain is rocked against the inside of the skull, but not hard enough to cause a diagnosable concussion. These hits are the most dangerous, as they can go undetected while leaving the brain hurt and even more vulnerable to damage later on.

A breakthrough 2013 study from UCLA regarding CTE treatment revealed a way to find indications of CTE in the brain while the patient is still living. This breakthrough would not only benefit athletes, but also improve public health, as many military personnel and victims of automobile accidents are also at high risk of these traumatic brain injuries. The knowledge of what to look for may lead to a cure or at least a treatment for CTE down the line. If nothing else, this knowledge will provide an opportunity to intervene and protect the people showing early symptoms.

CTE has affected athletes in mainstream sports for a long time, occurring in boxers since at least the 1920s under the name pugilistic dementia. It was thought to be almost exclusively a boxing issue, but recent research and studies have shown conclusive neuropathological evidence that the disease has been affecting football players for years in much the same way as boxers. Among the most prominent NFL players affected is Junior Seau, who fatally shot himself in May 2012.

The disease is likely affecting untold numbers of athletes across a wide array of sports. Most recently, it was discovered that Ryan Freel, a former major league baseball player who committed suicide in December 2012, was suffering from an advanced stage of CTE at the time of his death. This discovery was significant as it is the first known case of CTE from baseball. Freel sustained massive head trauma in 2007 when he collided with another outfielder and then bashed his head on the hard outfield warning track, and again in 2009 when he was hit in the head by a pickoff throw. Freel reported feeling random headaches and pains in his head after the 2007 collision.

The frightening aspect of CTE is that, currently, it can only be diagnosed post-mortem. This is because the brain tissues necessary to make an adequate diagnosis can only be acquired after death. Therefore, it is only possible to make diagnoses based on symptoms rather than scientific evidence. CTE manifests in a person’s lifetime by triggering memory loss, impulse control problems, intense depression, aggression and finally, progressive dementia. These changes in the brain can begin anywhere from immediately after the most recent brain trauma to up to decades afterwards. For this reason, mainly older and retired athletes have come forward to report their symptoms and issues with CTE. However, younger athletes are at risk as well.

While CTE currently cannot be conclusively diagnosed before death, concussions are an emerging field in sports medicine. Despite overall ignorance to the dangers of concussions, an increasing number of voices in the sports community are speaking out about the severity of brain trauma. These voices, catalyzed by the media coverage over the tragic stories of many athletes with CTE, as well as the Frontline documentary regarding brain trauma and the NFL, continue to grow, and as a result, changes are being made and questions are being asked about the safety protocols in sports.

UC Davis’ procedures

Many universities have started questioning previous medical protocol for handling concussions and brain trauma. Some have even suggested that players wear padded headgear on their heads in sports such as basketball, lacrosse and soccer, all of which have relatively high rates of concussions.

“Any way you can prevent early onset concussions and brain injury, do it,” said UC Davis’ Senior Athletics Director Nona Richardson. “My suggestion a couple of years ago was ‘Let’s evaluate and see if we can have some sort of soft headgear for our basketball players and for our lacrosse players,’ because we had a number of lacrosse players getting concussions. So if this is one way that we can help offset that, let’s do it.”

However, not all are sure that the preventative measures are effective. Some believe that proposed solutions such as headgear are simply a bandage on a much larger wound.

“After careful review, the Sports Medicine Committee finds no evidence that wearing this sort of [padded] headgear is beneficial to players, and is concerned that it might actually lead to more injuries,” said an official statement made by the U.S. Soccer Federation. “The Sports Medicine Committee is also concerned that the use of headgear in soccer may alter the game in ways that would be detrimental. For example, players may develop a false sense of security, play more aggressively, and not learn proper technique — thus potentially increasing the frequency of concussions. As an example, head and neck injuries have increased in ice hockey and football since the introduction of helmets in those sports.”

If this is the case, then there seem to be few options which administrators and trainers can implement to prevent concussions. One idea that has picked up traction is to change the rules of the game.

“The football rules this year [are] different for the NCAA to help prevent concussions. You’re not allowed to go [for] head-to-head [collisions] anymore,” said UC Davis’ Assistant Athletics Director Mike Robles. “The penalties are severe. You can get kicked out of the game.”

Despite the rule changes, the rates of concussions still remain fairly high. This is because rule changes can only protect players every so often. The rules cannot shield the players from the possibility that one of them takes a fall or gets tackled in a way which shakes up his or her brain.

Many in the sports community feel that concussions are not completely preventable. There are ways to lower the risks, but much like a torn ACL, concussions are simply a risk of playing sports.

“We don’t have a way of preventing concussions, but we do have a way of monitoring concussions,” said UC Davis’ Director of Sports Medicine Tina Tubbs.

For example, UC Davis has multiple layers of observation in regards to a possibly concussed athlete. This includes baseline testing (AXON testing) which occurs before players even take the field and allows the trainers to have numbers regarding the players’ cognitive function before any major incidents. Beyond this, the University has trainers on the field as well as a team doctor who constantly evaluates players who may have been concussed. After this testing, the doctor and team staff will determine whether it is a concussion.

“If we’re going to call it a concussion, there is no mild, medium or large concussion,” Tubbs said. “It just is a concussion or it is not.”

The treatment policy regarding a concussed player at UC Davis is that the athlete cannot resume physical activity for a week and a day. After this time, the staff requires the player to retake the AXON testing as well as undergo a CT scan if necessary. If the athlete passes the AXON test and shows no further concussive symptoms, the University waits another day to see if any symptoms reoccur. If not, the player is free to resume light physical activity, such as riding an exercise bike. After that, if no symptoms appear, the athlete is allowed to jog. It may take at least seven to 10 days for the athlete to get from the point of first restarting physical activity to full athletic participation. Thus, a concussed athlete is generally out for at least two weeks.

Beyond the concussion protocol, UC Davis athletics policy states that if a player has three concussions while at UC Davis, they will be retired, meaning that the player can no longer compete for the University.

Where do we go from here?

While the rules of the game have changed and most athletic associations have adjusted their organizations to deal with the dangers of concussions and brain trauma, some wonder whether these procedures are enough, or whether the owners, managers and administrators care enough to enforce them.

On Jan. 5, during one of the NFC Wild Card Playoff games, Green Bay Packers’ David Bakhtiari ran out onto the field for an extra-point attempt. However, he was in the middle of a concussion test, clearly violating the NFL concussion policy. According to NBC’s profootball.com, even though the NFL found the Packers to be in violation of league policy, there will be no fine assessed to the team or player.

Moving into the future, discussion about CTE and concussions can and should be continued. However, beyond the science of concussions and the protocols put in place by many organizations to prevent them, people must realized that athletes are humans — humans that are ultra-competitive and often times so driven to succeed that they lose sight of potential risks to their physical safety.

It is up to the coaches, trainers and league officials to understand the gravity of the situation and protect the athletes from themselves. They should emphasize the severity of concussions and discourage athletes from shrugging off head trauma for the sake of the game. One minute of play does not justify a lifetime filled with health and mental problems. At the end of the day, all the rules in the world can be implemented to help protect athletes from concussions, but there needs to be strict enforcement. Without it, the alarming trend of concussions and CTE-related problems will continue.

Great job to The Aggie staff for raising awareness about this important and timely issue. While stories like Jahvid Best’s are dramatic illustrations of the risks certain positions carry, keep in mind that every single time the ball is hiked at least ten linemen are involved in harmful subconcussive impacts as they battle for control of the all important line of scrimmage. If I recall correctly, that’s about 1,500 times each season. As the Frontline story makes clear, Mike Webster, whose autopsy played a key role in the discovery of CTE, was not a running back. Nor was Junior Seau. Lastly, however well they understand the gravity of the risks, no one should kid themselves that coaches, trainers, and league officials alone will protect athletes from this threat. This one is much bigger than that and it involves parents, principals, provosts, chancellors, presidents, reporters…and, there’s no avoiding it, each individual sports fan.