Chancellor, police chief, students weigh in on de-escalation policies of campus police

Following the March for Our Lives movement, nationwide marches that took place after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, Chancellor Gary May released a statement on gun violence in which he described feeling disturbed “by the violence that continues to plague our society.” May said he is “encouraged that UC Davis Police Chief Joe Farrow has made de-escalation training a priority for his campus officers.”

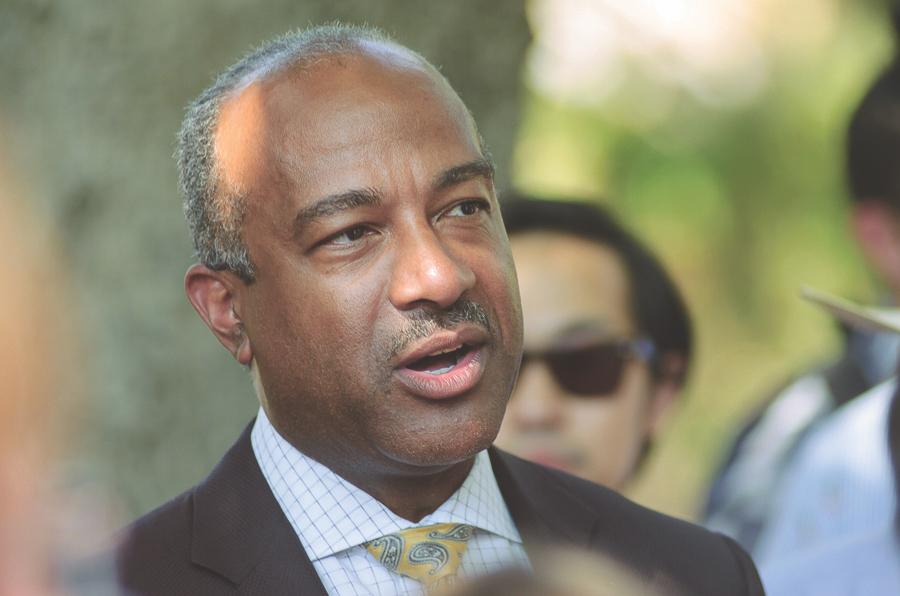

UC Davis Chief of Police Joe Farrow gave his definition of de-escalation.

“De-escalation is part of the way policing looks at officer-citizen contacts and de-escalation really started on the way we dealt with people with mental illness,” Farrow said. “We look at what is truly important, what we are trying to do and how we can take the police officer and citizen contact and resolve it in a way that is as close to mutually beneficial as possible. How do we have the citizen walking away and say, ‘That is fair, the officer has done their job?’ De-escalation is all about how officers train in a way where they calm rather than heighten situations.”

May responded to questions regarding the importance of de-escalation as a focus of UC Davis Police Department via email.

“UC Davis police officers are in contact with members of the public every day,” May said. “Fortunately, ‘use of force’ incidents are rare for campus police, but officers have to be prepared for incidents that can be stressful, unpredictable, fast-moving or pose a risk to the subject, officer or members of the public. It’s important that every such contact has the best outcome possible and that’s why this philosophy of de-escalation is important in modern policing.”

The chancellor also mentioned steps he is taking in order to make de-escalation a reality.

“All UC Davis police officers complete eight hours of training in responding to people

with mental health issues,” May said. “The department has committed to have all officers go through Crisis Intervention Training, the national standard for working with people in crisis, far exceeding required state standards. Additionally, the department is training officers in cultural diversity and hate crimes, implicit bias and in the human factors that affect how people react under stress. I’m committed to supporting the Chief and the department in providing the best training in these areas.”

Amara Miller, a graduate student pursuing a Ph.D. in sociology at UC Davis and a member of the UC Student-Workers Union (UAW Local 2865), said that the chancellor’s message is not assurance enough for her.

“I think it’s still a little vague: de-escalation training is wonderful and great but if it’s not coupled with policies that actually mean de-escalation is the first thing that cops are supposed to do, it’s not a guarantee that they’ll actually use the de-escalation training that they are given,” Miller said. “Not to mention the fact that there are no clear guidelines in any of these conversations about when cops have to have de-escalation trainings […] once they’re hired. It’s not a guarantee that it’s going to get to people that need it.”

B.B. Buchanan, a sixth-year Ph.D. candidate in sociology and another UAW 2865 member, was also not completely assured by the chancellor’s message.

“It’s a first step,” Buchanan said. “The problem isn’t just that there is not the right training, but rather research shows that when you have a weapon on your person, you’re more likely to use it. For example, British cops don’t go around with handguns, which means they are forced to rely on de-escalation training. Cops in the United States have de-escalation training that they don’t often utilize because their first response is lethal force. The problem isn’t with the training, it’s with the organization as a whole and it’s with the fact that American police view lethal force as reasonable.”

Police Chief Farrow mentioned that simply requiring de-escalation training is not enough in his view either.

“Our de-escalation program started here last fall when I got here,” Farrow said. “It’s ongoing. It’s not as simple as you go to a class and you’re cured, it is an ongoing systematic change that is reinforced through training, policy [and] supervision, and it never ends. For example, most of our officers had a form of mental illness training before I got here. The state standard is eight hours. They’re all receiving 16, 24 and 40 hours of training, and de-escalation training is part of that.”

Farrow said officers will “be going through procedural justice” — a class he has both taken and taught before — and “de-escalation training is part of that course.” He also said the department has a “roadmap and a very ambitious plan over the next year” to incorporate values from these kinds of classes.

“[The incorporation of values] is also being reinforced by the way we operate through policies and through training and guidance and the way we supervise,” Farrow said. “I don’t want to paint the illusion that everything changes because we go to a class, it has to be reinforced, it has to be deep-rooted in the people here.”

Miller discussed why UAW 2865 is pushing for demilitarization and de-escalation of UCPD in current contract negotiations with the UC Office of the President.

“If you’re a graduate student who’s a person of color on our campus or you’re Sikh or something where you’re targeted or racialized as being an enemy combatant by a militarized police force — even just going to work or going into your teaching room where you’re educating students can be potentially endangering,” Miller said. “If you have police out and about on campus and you’re targeted as being a terrorist or a thug, you are not safe in your workplace.”

According to Miller, UAW 2865 is requesting a number of specific policies in order to ensure the safety of its members and other students and faculty on campus.

“We’re trying to get more required trainings with specific time requirements of when police have to have these trainings,” Miller said. “We want more than just de-escalation training. We want to ensure that [police] have training on how to deal with mental health crises, how to address certain populations. We’re trying to make it so that they can’t use lethal weapons unless it’s something like a mass shooting. On everyday use, [police] don’t need to have a gun on [their] persons.”

Farrow described a number of ways in which his department has been looking into de-escalation strategies, including the fact that the department is moving beyond state minimum standards and seeking national accreditation.

“National accreditation is where you try to figure out what everyone else is doing and you try to achieve that,” Farrow said. “In order to do that, there are 476 standards you have to look at and that’s what we’re doing right now. We’re going to look at every policy, the way we train, the way we guide our people, what procedures we have in place, what procedures we don’t even have in place and we’re going to try to bring them into our department.”

Recognizing that past incidents with UCDPD have caused students and workers to distrust UCDPD, Farrow said that he and his department are working hard to gain that trust back.

“There are people that still remember the day that we had the pepper-spray incident — that was a violation of people’s trust,” Farrow said. “You can look at it any way you want, but at the very end of the day, the incident of itself was bad and it has painted a cloud over an organization for a long time. We have done a lot of good things to try to re-identify who we are and what we do, but I think we’ll never forget that incident. We should always remember that incident because that incident defined us one day, and we lost the trust of a lot of people, and we wounded the people we were supposed to serve. Now, we’re trying to move forward and not forget, but learn from what that felt like.”

Farrow pointed to this year’s Picnic Day as an example of police on campus providing a helpful service and ensuring safety, rather than focusing on writing citations and making arrests.

“We had a really good Picnic Day and it was all about de-escalation and training,” Farrow said. “At the very end of the day, we had thousands of people here and it was safe, it was fun, and there were very few officer contacts. We provided a service, but at the same time, if something bad was to happen, we were ready. We create a vision for our officers and they’re expected to follow that.”

Farrow said that he is committed to listening to student concerns and having productive conversations that will hopefully lead to mutually beneficial results for students, workers and the campus police department.

Written by: Sabrina Habchi — campus@theaggie.org