Apple removes screen-time restriction tools, citing privacy, while selling a wife-tracking app

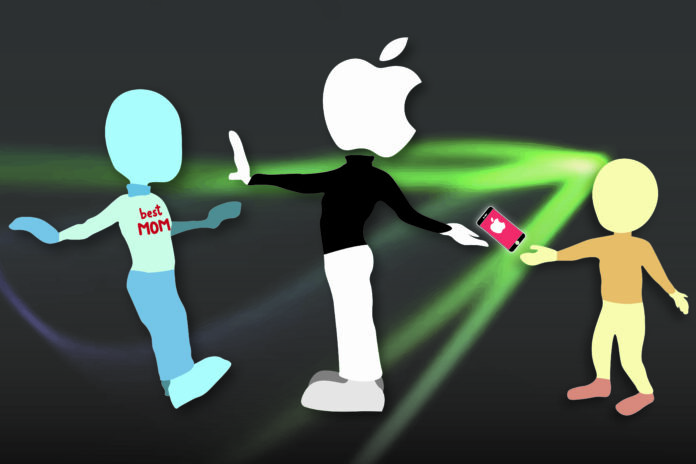

The New York Times recently published an article on Apple’s year-long campaign of purging and restricting parental-control apps that allow users to restrict their children’s screen time. In defense of this move, Apple spokeswoman Tammy Levine cited privacy concerns, alleging that the apps gathered intimate data on users, including their location. Conceivably, given Apple’s professed devotion to user privacy and safety, the company would display more concern over Absher, a wife-tracking app, being sold on the App Store. It hasn’t.

Absher, launched in 2015 by the Saudi government, has been widely popular in Saudi Arabia, which governs its female citizens under guardianship laws that essentially demote the legal status of women to that of minors and wards. Under these laws, every Saudi woman has a male “guardian” who must give their consent in order for her to get a passport, have certain medical procedures or get married.

Absher helps enforce these laws by allowing “guardians” to restrict women’s travel, providing them a tool to track women through their national ID cards or passports. The app provides an alert function, notifying men any time a woman under their guardianship goes through an airport.

Feigning ignorance of the app’s enforcement of guardianship laws would be futile at this point, as Apple CEO Tim Cook has already been made aware of the app in an interview with NPR. Here, he stated he had never heard of Absher, “but obviously we’ll take a look at it if that’s the case.” Advertised in Apple and Google stores as affording users the ability to “safely browse your profile or your family members, or [laborers] working for you, and perform a wide range of eServices online,” this is plainly and painfully the case.

A Saudi woman fleeing to Australia from her family was able to do so by discreetly giving herself permission to travel through her father’s phone. Without first secretly giving herself consent to travel and then turning off Absher’s notifications, she would not have been able to leave.

The fact that Absher serves as a real obstacle toward not only gender equality within Saudi Arabia, but also an obstacle for women attempting to flee abusive households makes Apple complicit in this oppression.

The mere existence of this app alone undermines any claim Apple can make about wanting to protect user privacy from screen-time and parental-control apps. But the lack of response from Apple following Cook’s interview obliterates an already-flawed, nonsensical attempt at reasoning.

Amidst the controversy sparked by the Times article, Apple has affirmed its commitment to fighting screen addiction with very little action toward that end. Apple has made it difficult to use even its own screen-time tools and enforce time restrictions on social media platforms. When users are notified that they’ve reached their time limit, they’re only given the option to click “Ignore Limit.”

Apple’s tool also only works for parents if all family members have an iPhone. Its new restrictions on screen-time and parental-control apps only allow for blocking adult content on its Safari web browser and some apps, but not on others like Twitter, Youtube and Instagram — the most popular and addicting. They’ve also restricted and removed apps allowing adults to fight their own iPhone addictions.

Apps like Freedom and OurPact, stripped from Apple’s app store, have reached out to the company in an attempt to comply with their guidelines and get their apps on the store again. Although developers have been more than willing to accomodate, Apple has been unwilling to instruct them on how to do so.

Despite its claims to the contrary, Apple clearly isn’t interested in fighting phone addiction, or ensuring privacy for that matter. In exacting sly methods to remove and restrict the functionality of screen-time apps and tools, Apple actively frustrates attempts at reducing addiction to tech in the youngest generation. Children are most susceptible to phone addiction — a fact that all, especially tech-giants, know well. If Apple can reach its market base at a younger age, it can instill both customer loyalty and addiction from the outset of a child’s technological experience.

In the face of its coercive activities and the sale of Absher, clearly violating the privacy guidelines that Apple values so highly, citing privacy protection is an absurd attempt at moral high ground. The moral rectitude Apple professes on this issue is not merely insulting to the public’s intelligence — it’s abhorrent.

Written by: Hanadi Jordan — hajordan@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.