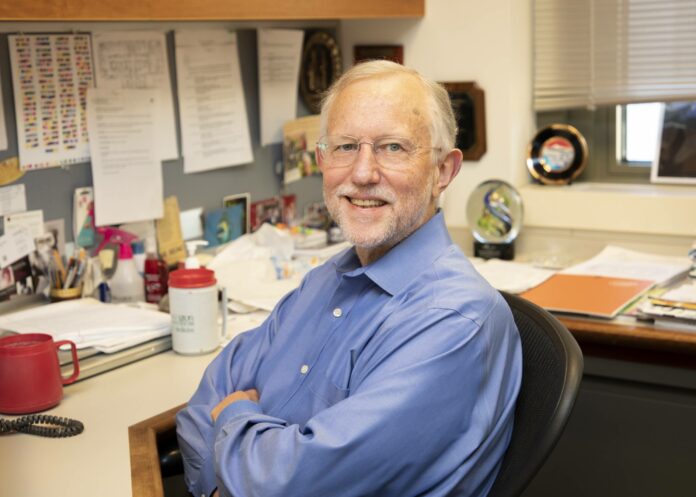

Professor of virology recognized for discovery of the hepatitis C virus

When Charles Rice, a professor of virology at The Rockefeller University, heard his landline ringing at 4:30 a.m., he figured someone from his laboratory was pulling a prank on him. But when the voice on the other end of the line mentioned the names of his co-Laureates and hepatitis C, Rice’s initial irritation turned into shock and disbelief. He had won a Nobel Prize.

“It’s not something you can readily go back to sleep after hearing,” Rice said.

After years of work in the field, Rice has been honored with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of the hepatitis C virus. As explained in an article by The Rockefeller University, Rice was responsible for finding the missing sequence on the hepatitis C genome and demonstrating that this virus was sufficient enough to cause hepatitis C in animals. He also developed a way for the virus to replicate in cells without producing the disease itself, allowing researchers to develop drugs inhibiting replication using his technique.

James Letts, an assistant professor in the department of Molecular and Cellular Biology at UC Davis, explained that hepatitis C is a chronic infection, which leads to serious conditions such as liver cancer or cirrhosis.

“Especially these days with the pandemic, we really understand how devastating these viruses can be and it’s very rare to actually be able to cure one,” Letts said. “[Rice’s] work really paved the way to develop these types of treatments that can essentially clear the virus from the system from a human being.”

Before his involvement with virology, Rice studied zoology at UC Davis as an undergraduate student. Even now, he still has fond memories of his time at Davis: working in the library, sitting on the lawn in the Quad when the weather was nice and living with his close friends on Rice Lane. According to Mark Winey, the dean of UC Davis’s College of Biological Sciences, Rice had mentioned in previous interviews that participating in research during his early academic career at Davis helped him to see himself as a scientist.

“That hands-on experience and the opportunity to work in a lab or do field work is really important in helping students find their path,” Winey said.

Rice’s interest in viruses was sparked when he was placed in a virology lab during his graduate studies at the California Institute of Technology. According to Rice, he was looking to be placed in a developmental biology lab using sea urchins, as he served as an undergraduate researcher in a similar laboratory at UC Davis, but was placed into this lab by chance.

“I might have ended up, if I’d gotten placed in a different lab, doing something completely different,” Rice said. “It was kind of a random event.”

As he continued his career in virology at Washington University, Rice conducted genetic analyses on the yellow fever virus, which is part of the Flaviviridae family. When research in 1989 came out about the genome structure for non-A, non-B hepatitis—now known as hepatitis C—his lab discovered that the genome sequences were very similar to that of a flavivirus. Rice recalled that when he first began working with the virus, hepatitis C research was unpopular due to the inability to grow the virus in a culture in the laboratory. But by the end of the 1990’s, interest in the virus grew and most of his laboratory came to work in this field.

Since then, Rice has opened his own laboratory of virology and infectious disease at The Rockefeller University researching the mechanisms of flaviviruses. Although Letts only worked there for three months when he was a graduate student, the two still keep in touch. Letts said that Rice has always been supportive of him and his career at Davis, and even wrote him a recommendation letter for his current job. Alison Ashbrook, a postdoctoral fellow currently working in Rice’s lab, also spoke of Rice’s encouraging spirit, stating he pushes people to hold their own convictions and to be independent.

“One of Charlie’s best attributes is how much he values students and educating the next generation of scientists,” Ashbrook said via email. “He sees limitless potential in anyone with the curiosity and discipline to solve the scientific mysteries that lurk around every corner. Whether you’re in Charlie’s lab or another, if you’re passionate about science, he will always root for you!”

Ashbrook became aware of Rice’s work after discussing a publication from his lab during graduate school. It was through this paper that she formed her initial opinion that Rice was an authentic and rigorous scientist. Inspired by the precision of the study and the integrity of reporting an unexpected result, she went on to read more of his papers and was amazed by the quality and breadth of his work.

“Charlie, first and foremost, is a scientist,” Ashbrook said via email. “He eats, sleeps, and breathes science. He is one of the most curious scientists I know and is excited by almost any scientific question, which is evident by the really diverse projects ongoing in the lab.”

For undergraduate students who are currently pursuing a career in research, Rice advised that you have to love what you are doing. He described it as ‘mind-boggling’ that researchers are lucky to be able to explore the things they are interested in while also pursuing it as a career. Similar to how he experienced many obstacles between the time in the mid-1970s when word of the virus began to spread, to the 2010s when there is now a cure for hepatitis C, he encourages students to enjoy the journey despite its ups and downs, rather than focusing on the endpoint.

“I think you just have to love it. You just have to,” Rice said. “If you find something you really have the desire to do and the passion for, you’re going to do the best job. You’re going to be thinking about it all the time. You’re going to be unstoppable when you encounter obstacles, which is true in research.”

Written by: Michelle Wong — science@theaggie.org