UC Davis partners with the Public Health Institute’s Child Health and Development Studies

Michele La Merrill, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of Environmental Toxicology and a co-leading author of the recent study, explored the effects of widespread chemical exposures in the 1960s on individuals born during the time of use, as well as on subsequent generations.

This study specifically focuses on DDT, a persistent organic pollutant (POP).

“In our past work, we’ve shown that in humans and in mice, DDT exposure during pregnancy can have effects on the risk of obesity and breast cancer in the female offspring,” La Merrill said. “Another group of individuals did work where they showed that pregnancy exposures to DDT in rats caused obesity in even further-out generations of the rats.”

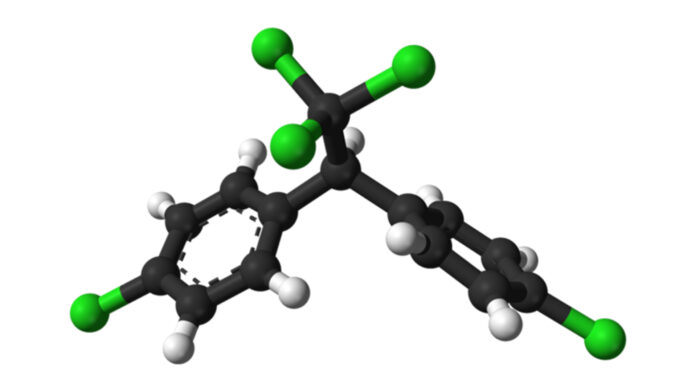

DDT is a commercial product consisting of p,p’-DDT, an insecticide, and an o,p’-DDT, a low-level contaminant, according to the study.

“There are multiple chemical structures that are related to DDT exposure,” said Barbara Cohn, the director of the Child Health and Development Studies (CHDS) at the Public Health Institute (PHI). “These different DDT-related compounds have different structures, which have different endocrine actions.”

The researchers measured o,p’-DDT levels because it “may be the best biomarker for perinatal exposure among these related compounds in humans,” according to the study.

“One of the implications is that even though our country banned the use of DDT in the early ‘70s, its effects are still with us as a country as its legacy continues to shape our health risks,” La Merrill said. “Another area of our research has been showing that people who migrated into the U.S. from areas where DDT has been in use for manufacturing have much higher levels of DDT in their body.”

Overall, the researchers’ findings support their initial hypothesis. The data suggests that “ancestral exposure to environmental chemicals, banned decades ago, may influence development of earlier menarche and obesity, which are established risk factors for breast cancer and cardiometabolic diseases,” according to the study.

“We were able to do one of the very first three-generation studies that actually looked at exposure during the critical window of development,” Cohn said.

O,p’-DDT levels in the grandmother generation were associated with an increase in obesity and earlier menstruation cycles. Additionally, an egg’s exposure to o,p’-DDT can alter the risk of breast cancer across generations.

“A synthetic man-made chemical that was used for good purpose—no one was trying to hurt anyone—had unintended consequences, including cancer, reproductive problems and obesity,” Cohn said. “The idea that [DDT] would be the only chemical in the whole planet that could do that never particularly would be a reasonable assumption. It is really hard to figure out which the others are.”

La Merrill said that researchers are actively working on answering how this multigenerational observation is biologically plausible.

“We’re currently pursuing research to see if there are common biological mechanisms that come up throughout this,” La Merrill said. “One of the mechanisms that we’ve looked at seems like DDT exposure makes it harder to burn calories, to keep our body warm. It basically slows our metabolism.”

Alternatively, Cohn said that next steps include finding a biomarker of risk that could be reversible.

“The question is, could we find a marker like that, that we might be able to change even in the people who have these ancestral exposures that couldn’t be avoided,” Cohn said. “It’s a simultaneous problem of protecting the next generation, but also trying at least to look at or find a way to intervene on the problem in the current generation.”

As Cohn explains, high levels of cholesterol—defined to be a “waxy, fat-like substance” by the Centers for Disease Control—is an example of a biomarker. Over time, people have developed methods to reduce these levels, which have resulted in a decreased risk of heart disease.

“One of the ways we could avoid this going forward is to screen chemicals that are meant to be used by people, or released in the environment, for their ability to influence the way we burn calories as an indicator for this risk in the future,” La Merrill said.

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) was among one of the organizations that supported this research.

“The knowledge generated by the research will be valuable to regulatory agencies and policy makers responsible for ensuring that agrochemicals needed to maintain agricultural productivity do not have adverse health and environmental impacts,” said senior science staff members in the NIFA’s Institute of Food Production’s Plant Protection Division, via email.

In their statement, NIFA said that they will continue to invest in research that develops agricultural management strategies that not only protect profitability for farms and ranches, but decrease human health and environmental risks.

“The legacy [of DDT] not only continues from the perspective that all the people in America who had ancestors that lived here when DDT was actively used they’re at risk, but also people who are immigrating from other countries where it’s been more recent probably have even higher risk,” La Merrill said.

Written by: Aarya Gupta — science@theaggie.org