Director Chloe Zhao’s damning look into the lives of itinerant workers brings attention to a little-known American subculture

Full disclosure: I love the desert—and I also love neo-Westerns. So naturally, I already had some preexisting bias toward the cinematic artistry that is “Nomadland” prior to watching it. But I think such partiality has proven justified. While it’s certainly not in the same category of “No Country for Old Men” or even “Wind River,” this unassuming narrative project paints an accurate, and at times disheartening, picture of life in the modern American West.

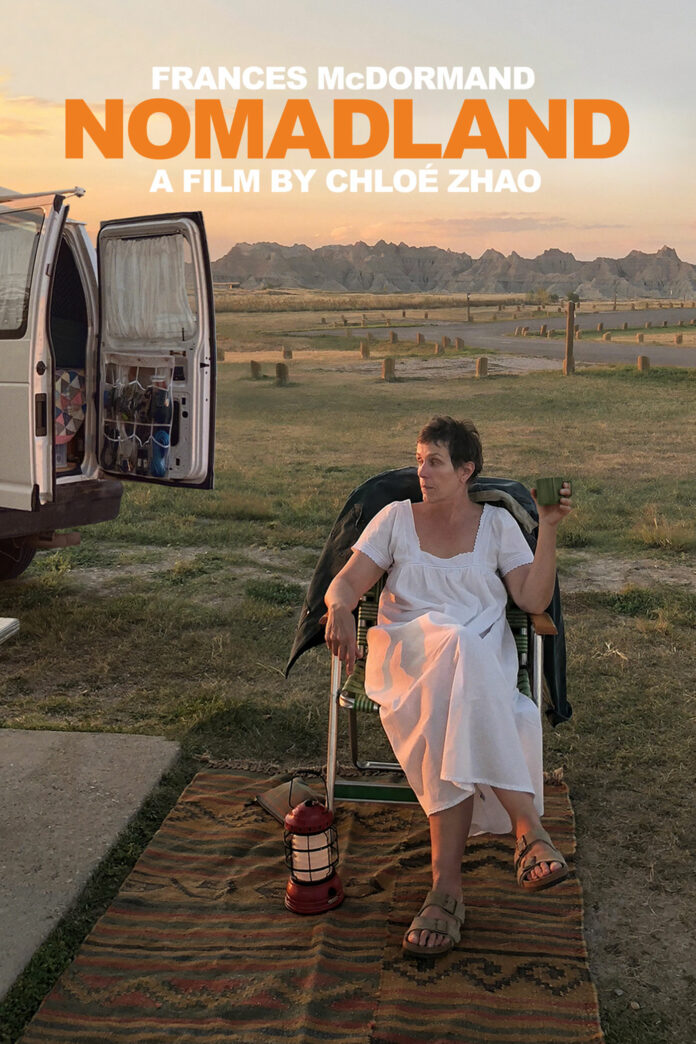

Set just after the Great Recession, “Nomadland” follows 60-something-year-old Fern (played by Frances McDormand) as she leaves her recently boarded up company town of Empire, NV, in search of migratory work. Fern’s departure from remote northern Nevada takes her on a van-dwelling adventure across the modern U.S., as she works temporary odd jobs ranging from an Amazon warehouse sorter to a national park worker. Based on the 2017 nonfiction novel “Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century” by journalist Jessica Bruder, the film blurs the line between reality and fiction, combining a tiny cast of actors with real life characters. Likewise, this strategy—a routine feature in filmmaker Chloe Zhao’s cinematic portfolio—leaves the picture feeling one-part documentary, one-part entertainment.

Being only Zhao’s third feature film, “Nomadland” joins “Songs My Brothers Taught Me” and “The Rider” in the Beijing-born director’s burgeoning filmography. The three pictures are comparable in that they can all be vaguely classified as neo-Westerns, utilizing themes of solitary characters set against the aesthetic background of the Western U.S. But what they lack in the traditional motifs of guns and gold, they more than make up with nuanced inquiries into the lives of the people who call these places home. In her first two films, the subjects are largely rural Native Americans. In “Nomadland,” they’re itinerant Americans of all pasts and backgrounds.

By its end, “Nomadland” leaves the viewer with a deeply cynical and nihilist feeling. Not so subtly hidden beneath the gorgeous shots of the American West—ranging from the wooded forests of California’s Mendocino coast to the rugged rock formations of South Dakota’s Badlands National Park—is an ultimately foreboding testament that highlights the woes of American capitalism. Fern, and the many colleagues like her, are left without a secure social safety net as they wander seasonally from job to job. This vulnerability only seems more apparent whenever tragedy strikes in the film, be it terminal cancer or simple car issues.

While the “nomads” form their own distinct community—one notable scene features Fern comfortably wandering around a new RV camp in the morning and generously offering her freshly brewed coffee to strangers and friends alike—there’s still an understanding that many of these friendships are inherently fragile, lasting only as long as the employment opportunities allow. Coming and going like the seasons themselves, there is only so much time for socialization. Even toward the end of the film, when Fern visits her implied love interest Dave (played by David Strathairn) at his family home in Northern California, there is still a feeling of social frailty. This anxiety is confirmed when Dave finally decides to settle down to more permanent fixtures, and Fern promptly turns down his offer to join him. Despite the film’s insistence that nomads are never truly alone because they will always “see [each other] down the road,” the feeling of isolation in this story is largely inescapable.

Although a far cry from being an overtly political film, “Nomadland” depicts modern society by evoking imagery of so-called “American carnage,” displaying hollowed out, turn-of-the-century industrial towns displaced by the installation of Amazon shipment warehouses. By its end, “Nomadland” is a film of two folds. It is equal parts boring and beautiful, charming and disheartening. So while nobody is likely to cement this movie as the next big blockbuster, Chloe Zhao’s combination of gorgeous cinematography and real life personalities brings a segment of American society to light that is largely ignored by Hollywood, and this feat is worthy of praise indeed.

Written by: Brandon Jetter — arts@theaggie.org