UC Davis researchers strive to understand “hugely problematic” catastrophic injuries in racehorses

By MARGO ROSENBAUM — features@theaggie.org

With bottles of coat shine and thin layers of sweat, racehorses glitter in the sun and dance on spindly legs across the soft-dirt track. Jockeys adorned in colorful silks are slung onto the backs of skittering two-year-old horses as they parade past the grandstand at a jiggy trot. White-eyed, nostrils flared and still dancing, the horses are ready to run.

Up in the grandstands, the smell of the synthetic track burns in the noses of onlookers. Kids shriek and point to their favorite horses; parents soothe them while taking notes in their betting booklets. Odds flash on the screen — 9-5, 3-1, 7-2 — as the horses step into the starting gate. Members of the crowd rush to the betting booth; cash flows from their hands as they cast their bets.

The bell clangs, and the horses are off.

A day at the races excites many people interested in racing, especially young Dr. Mathieu Spriet, who grew up going to the races in France with his father Alain and sister Sophie. Spriet has been surrounded by horses ever since he was a kid — his grandparents, Etienne and Jacqueline Savinel, bred sport horses as a hobby on their farm, Les Pres de Here, Rue in Somme, France.

Spriet always enjoyed going to the races as a child, but at one race at Hippodrome du Croise-Laroche, Marcq-en-Baroeul in Nord, France, that all changed. When he was just under 10 years old, Spriet witnessed a horse break down and be pronounced dead on the track.

“I remember that one time, when a horse fell,” Spriet said, reflecting on the experience. “That was my first introduction to breakdown in horse racing as a kid.”

Spriet said that the horse likely suffered from a severe limb fracture, which the racing industry and veterinarians call a catastrophic injury or breakdown: a fracture that marks the end of a horse’s racing career and, often, their life.

Unknown to Spriet at the time, these deaths are not uncommon in horse racing. In the 2018-19 racing season, 144 horses died at racetracks under the California Horse Racing Board’s (CHRB) jurisdiction. The number dropped to 72 in the 2020-21 season, but many say there are still too many deaths.

While many race attendees never see one of these injuries firsthand, this experience was one reason Spriet became a veterinarian. Spriet, among many others at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, works to understand why these injuries happen and how to prevent them.

“I remember […] my dad having to explain to me that this horse was dead,” Spriet said about seeing the horse breakdown. “As a kid, it was just super hard.”

These catastrophic injuries afflicting the racing industry are the result of cumulative mild overuse, similar to shin splints developing over time in runners, according to Dr. Ashley Hill, the associate dean of veterinary diagnostic laboratories at the California Animal Health & Food Safety Lab System (CAHFS).

Hill’s coworker Dr. Francisco Uzal, a professor of veterinary pathology and the branch chief of the CAHFS’s San Bernardino laboratory, said catastrophic breakdowns often involve fractures that divide the bone into two, three or even many pieces.

“When a limb is overused, particularly at a younger age, little microfractures occur in the bone,” Uzal said. “If they are not detected and the animal is not rested, that’s when a catastrophic fracture [occurs].”

Soon after Spriet saw the horse break down, he wrote in a school paper that he wished to become a veterinarian to fix the same fractures he witnessed at the horse race. But when he entered veterinary school, he decided to focus on breeding, following in the footsteps of his grandparents. Later on, he changed his mind and refocused on lameness and diagnostic imaging.

Spriet earned his veterinary degree in 2002 at the Ecole Nationale Veterinaire de Lyon in France and his master of science (MS) at the University of Montreal, St. Hyacinthe in Canada in 2004. After completing his radiology residency at the University of Pennsylvania, he came to UC Davis in 2007.

Now, as a professor of diagnostic imaging at UC Davis, he worked on a positron emission tomography (PET) scanning device for horses and strives to detect early signals that cause these catastrophic injuries.

“Breakdown in racing [is] a big issue,” Spriet said. “It’s not new. It’s not a California thing … I saw that in France when I was not even 10 years old. It’s something that is important to work on and there are a lot of things that can be done.”

“Hugely problematic” injuries plague the racing industry

Since 2014, Horseracing Wrongs, a non-profit devoted to ending horse racing, and Patrick Battuello, its founder and president, have confirmed over 8,000 horse deaths at U.S. racetracks by filing Freedom of Information Act Requests. However, not all data on horse deaths are made available to the non-profit, such as deaths at private training facilities and farms. The group estimates over 2,000 horses die at U.S. racetracks every year, Battuello said.

It is not just animal advocates who believe too many horses are dying. Industry members and researchers know catastrophic injuries are happening with high incidence.

Cecil B. DeMille’s grandson Joe Harper, the former child Hollywood star who has been the director, president and CEO of the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club since 1978, agrees that too many horses die from racing.

“We’ve seen this industry, and the dark side of it is that horses break down and have to be euthanized […] in our opinions, it was happening too much,” Harper said.

Like Spriet, Dr. Jen Symons, who completed their mechanical and biomedical engineering Ph.D. at UC Davis, studies racehorse injuries, specifically the effect of racetrack surfaces on horse limbs and injury.

“Musculoskeletal injuries for racehorses are hugely problematic,” Symons said. “They happen with an incidence that is concerning.”

But some say these injuries are inevitable consequences of the sport, including Dr. Ferrin Peterson, a professional jockey and veterinarian who attended UC Davis for her veterinary degree. Peterson compared injuries in racehorses to those sustained by human athletes.

“When you’re training at the top level, there’s going to be injuries because you’re just asking so much out of your body,” Peterson said. “You obviously can’t prevent all of them.”

But some say these injuries are more dangerous than for humans. Severe catastrophic injuries usually necessitate euthanasia, and Symons said that as an owner, rider and lifelong lover of horses, this part of their job was particularly challenging.

“That’s troublesome for anybody, but I think particularly for me because I really loved horses,” Symons said.

The No. 1 school of veterinary medicine’s role in the industry

As more people recognize the high incidence of racehorse mortality, researchers devote their work to preventing injury. As the No. 1 school of veterinary medicine in the country, UC Davis conducts research on general equine welfare and safety, and many researchers have a special focus on racehorses. The school says it is “committed” to its partnerships with the horse racing industry and “supports” the research efforts of the California Horse Racing Board (CHRB) and industry stakeholders to improve safety in the racing industry, according to a press release.

Through research on racetrack injuries, imaging technology, drug testing and postmortem examinations, UC Davis addresses challenges that have been present in the industry since the beginning.

Harper has been involved in racing for over 45 years and saw the growth of UC Davis’ relationship with the racing industry — the two have been “holding hands” for a long time, he said. Harper, among other individuals in the industry, encouraged UC Davis to study Thoroughbreds, explaining that racing interest groups would support their research. As a result, what is now known as the Center for Equine Health (CEH) was formed in 1973.

CEH’s website states that it was “originally commissioned by the horse racing industry to study problems faced by performance horses and identify ways to protect them from catastrophic injuries.” Since then, CEH has grown to include most of the equine research at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.

Individuals in the industry form CEH’s advisory panel, with Harper serving as its former chairman. “Joined to the hip,” the relationship between the CHRB, UC Davis and the horse racing industry has been “great” since its start in the 1970s, according to Harper.

The school is more tied to the racing industry than some may realize. Dr. Jeff Blea, the equine medical director for the CHRB, is employed by UC Davis but loaned to the racing commission. The equine medical director has no oversight responsibilities within the veterinary school or hospital.

Under California law, the equine medical director advises and is a member of the scientific advisory committee at the Kenneth L. Maddy Equine Analytical Chemistry Laboratory, housed at UC Davis. The equine medical director acts as the primary advisor to the CHRB for horse health at the lab.

Since 1990, UC Davis has led California’s postmortem examination program, receiving funding from the CHRB and CEH, among other sources. Every horse that dies or is euthanized at CHRB racetracks and training facilities must undergo a postmortem exam — also known as a necropsy — through CAHFS.

The Veterinary Medical Board temporarily suspended Blea’s license in January in light of a controversy. The California Horse Racing Board removed him from the investigation of the death of Medina Spirit, a Kentucky Derby winner who died unexpectedly last year at Santa Anita Park in Arcadia, CA. Blea was also placed on administrative leave by UC Davis due to the suspension of his veterinary medical license.

UC Davis veterinarians, including Uzal of CAHFS’s San Bernardino lab, performed the necropsy and found no definitive cause of death for Medina Spirit although heart failure is suspected. Many say this was not surprising.

“Equine sudden death cases while racing and training are an internationally recognized phenomenon and are very frustrating as the definitive cause of death is found in only approximately half of all cases despite the considerable pathological and toxicological effort,” a press release from the CHRB reads.

Necropsies and drug testing provide answers for horse deaths

About 80% of racehorses necropsied at UC Davis have been euthanized because of catastrophic fractures, according to Uzal. In those necropsies, veterinarians study the horses’ bones to document fractures and to characterize preexisting conditions that could predispose the horses to break down.

“We really don’t think that the great majority of cases are accidents that just happened; we think that in most cases, there are predisposing factors that can be prevented,” Uzal said.

In the past 10 years, the number of horses necropsied at CAHFS dropped from around 300 to less than 100 per year, according to Uzal. This may be due to the work that the CAHFS lab, Stover’s lab and Spriet are doing, studying the prevention of catastrophic breakdown at UC Davis.

The Kenneth L. Maddy Equine Chemistry Laboratory is also a part of CAHFS and operates as the CHRB’s primary drug-testing laboratory. The laboratory evaluates each sample for more than 1,800 substances and annually tests more than 40,000 samples from California racehorses. Dr. Heather Knych oversees research efforts within the Pharmacology section of the Maddy Lab.

In the racing industry, the goal of drug testing is to protect the safety and welfare of horses and jockeys, Knych said.

With the high incidence of betting in horse racing, testing is also important to protect the public interest in the sport. Testing helps to ensure “a fair and level playing field” in a race so no horses have an unfair advantage, or “at least not one that’s related to potential administration of a drug,” Knych said.

Knych also leads research to improve horse health and welfare by studying how nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are used to treat musculoskeletal inflammation, are processed and cleared in horses’ bodies.

She also studies methods for detecting these drugs in horses. Racing committees set regulations to ensure these horses are not competing with high levels of drugs that could mask injuries that would otherwise keep horses from competing well, Knych said.

Studies of catastrophic breakdown

Outside of necropsies and drug testing, the CHRB was always interested in the results of their research at UC Davis, Symons said. The CHRB wanted to know how to best implement their findings into policy and recommendations.

CHRB Executive Director Scott Chaney said in his December monthly report that new regulations at California tracks will “promote [animal welfare] with the goal of further driving down the incidence of catastrophic injuries.”

With goals to decrease horse deaths and injuries at their tracks, CHRB reported a 50% decline in racehorse deaths in California between the 2018-19 and 2020-21 racing seasons.

UC Davis reports that “decades-long efforts” between the CHRB and the school have contributed to the downward trend in horse fatalities at racetracks since 2005. At the same time, however, fewer racehorses are being bred and raced in recent years.

Dr. Susan Stover, the director of the J.D. Wheat Veterinary Orthopedic Research Laboratory at UC Davis, is one person devoted to studying racetrack safety. Her work focuses on studying racetrack surfaces and bone changes that precede fractures and put horses at risk for catastrophic breakdown.

Symons worked with Stover for their Ph.D., studying how horses run differently on dirt, synthetic and turf surfaces. Softer tracks were less injurious, they said.

Dr. Jacob Setterbo, who completed their biomedical engineering Ph.D. at UC Davis with Stover, also studied racetrack safety, creating a track-testing device and “track in a box” system to evaluate track surfaces. Based on his work with Stover, many tracks replaced their dirt tracks with safer, synthetic surfaces.

“It was good that tracks were willing to redo their entire track for the chance that it’s going to help with the safety of the racehorses,” Setterbo said.

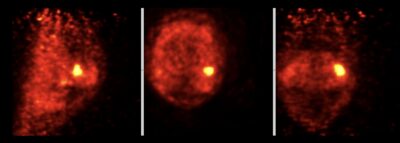

As a diagnostic imaging professor, Spriet is also able to promote racehorse safety, since the standing PET scan can help veterinarians identify horses at risk for catastrophic injury. Spriet said he commonly focuses on imaging horses’ front limbs, but sometimes the hind or all four are imaged, depending on the injury.

Spriet said that trainers used to say their horses broke down in accidents, such as after taking a bad step or tripping in a hole, but new research shows this is not the case. Injuries leading to breakdown oftentimes accumulate over time and are preventable if recognized early and the horse is properly rested.

By catching these predispositions to injury early on, horses can be rehabilitated and safely brought back to train and race. These low-grade injuries are usually seen after a horse has already broken down, but Spriet wants to catch them before the catastrophic injury occurs.

With 3D imaging, PET scans show bone weaknesses unseen in MRIs, particularly in the sesamoid bones of horses — the area most involved in the breakdowns, Spriet said. If he sees a few telltale signs on a scan, he knows these horses need a break from racing and training.

“There [are] some horses that will show signs, and if you see that a horse has some issue or is limping, it’s probably a horse you should not push on the track,” Spriet said.

Performed at UC Davis in 2016 by Spriet, the first PET scans required horses to undergo general anesthesia, which is said to have potential dangers for their health. With these risks, horse owners were not as willing to scan their horses, especially if they were healthy.

“Horses, unfortunately, break their legs on the racetrack, but horses are pretty good at breaking their legs in any situation,” Spriet said.

This presented challenges for Spriet, as he wanted to scan healthy horses at tracks like Golden Gate Fields in Berkeley, CA to understand the bone patterns that proceed breakdown. Spriet realized that he needed a scanner for standing horses that would not require general anesthesia.

In 2019, this scanner was developed by Brainbiosciences and Longmile Veterinary Imaging. Spriet said it could analyze horses lacking “specific issues,” since some horses show signs of breakdown, but others do not. A “big frustration” in the racing world is that some horses “look really good until they break.”

By scanning horses that are not showing signs of injury, Spriet hopes to understand the few that are breaking down. A small portion of “normal horses” have abnormalities that warrant Spriet’s recommendations for rest and rehabilitation.

“I mean there’s no question; there [are] too many horses breaking down,” Spriet said. “But when you look at the statistics, it’s ended up [that] the national average is 2.5 per 1000 starts. So that’s not easy. That’s not easy to find 2.5 in 1000 to sort them out.”

Research funded by interest groups benefits all horses

While many researchers at UC Davis — including Knych, Spriet and Stover — focus their research on racehorses, they hope their work impacts all horses.

“My research lab is within the drug testing lab for racing in the state of California, so that’s the industry we serve,” Knych said. “However, I conduct all of my studies with the intent of providing information to all performance horse disciplines. Furthermore, it is my goal to provide information that clinicians can use to treat backyard horses.”

Spriet’s work has been largely funded by the racing industry. By late 2018, Spriet and Brain Biosciences had developed the idea for the standing PET scanner, but needed funding. At the time, more people were becoming aware of catastrophic breakdowns in horses.

In 2019, 37 horses died at Santa Anita Park. The Stronach Group, which owns Santa Anita Park, donated half a million dollars to Spriet’s research to develop the standing PET scanner, and in return, the first scanner is owned by Stronach and housed at Santa Anita.

“It came pretty nicely together that we had an idea to try and prevent [horse deaths], and they had a problem that they wanted to fix, and that’s how it started working together,” Spriet said.

Now, five scanners are in operation, located at Santa Anita, the University of Pennsylvania, UC Davis, Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital in Kentucky and the World Equestrian Center in Florida. With about 100-200 scans completed annually at each site, close to 1,000 scans in total have been compiled thus far. By the end of 2022, three more PET scanners will be installed across the U.S. and two more are planned for installation in 2023.

Animal advocates say this research is not enough

Will research, testing and veterinary care really improve safety for racehorses? UC Davis seems to believe so, but some anti-racing advocates, such as Elio Celotto, the campaign director for the Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses (CPR), think otherwise.

“The reason why [researchers] are doing this research is not out of welfare for the horse, it is out of ‘how can we get more out of the horse?’” Celotto said. “So certainly, the work is being done on how you can avoid or sustain injuries, but it’s only so they can make more money out of them.”

However, not everyone agrees. Horseracing Wrongs’ Battuello said that regardless of what research is completed, all racetracks must be shut down and the industry must be eradicated.

“My question is always to anyone who would defend horse racing: you tell me what your acceptable loss ratio is?” Battuello said. “How many dead horses are you comfortable with? For a $2 bet? I always put it back on them.”

Since CPR’s start in 2008, the Melbourne-based animal welfare group has partnered with Battuello and Horseracing Wrongs to campaign for horse welfare and hold the racing industry accountable.

“It is a despicable industry, but of course, it had to be when you’re [to combine] when people try to make money out of animals,” Celotto said. “There’s always going to be exploitation and abuse of those animals.”

PETA, CPR, Horseracing Wrongs and other animal advocacy groups all condemn horse racing and call for its ban.

“The only acceptable outcome for CPR is for horse racing to be abolished,” Celotto said. “And we believe that one day that’ll happen.”

Celotto has noticed changing attitudes toward horse racing throughout the years. It is no longer considered “the sport of kings,” he said.

“Even people that worked in the racing industry have contacted us to say that they knew what was going on, that [they] needed somebody to actually say it,” Celotto said. “They’ve realized that as much as they love horse racing, they love horses more and have chosen to not support [the] sport anymore.”

Changes in the industry

Spriet understands concerns about horses breaking down at racetracks, but he does not see banning racing as the answer.

“It’s legitimate that people have this concern, being worried about what happened to horses dying on the track,” Spriet said. “It’s pretty horrible, pretty tragic, and we need to prevent that.”

Instead, he said that further research and regulations will protect horse safety and reduce these deaths.

“If you stop horse racing, that’s the worst thing you can do to the horse,” Spriet said. “What’s going to happen to all these horses? What’s going to happen to all the people involved?”

Symons sees the racing industry as “representative of different positions of resources.”

“There are some racehorses that live better than you and I do, and there are some that live pretty rough lives,” Symons said.

Spriet agrees, saying that there is a “misconception” that all horses are being pushed to their limits. He believes the “vast majority” of grooms, trainers, exercise riders, jockeys, trainers and owners have their horses’ best interests in mind.

“It’s a fascinating world where people are just fully devoted and their work all day long is to take care of these horses [and] have them in the best condition for racing,” he said. “There’s a whole population that really lives for the horse.”

After being involved in the sport for over 45 years, Del Mar’s Harper said he has noticed a change in the industry’s culture. Many trainers do not try to get “one more race” out of their horses any longer.

“In order to do that, we have to really focus our efforts on the health of the horse rather than the business at hand,” Harper said.

At Del Mar, veterinarians monitor every horse during morning training and races to prevent injured horses from racing. He wants to make the track as safe as possible to ensure the longevity of Del Mar Thoroughbred Club.

“Let’s face it. If you pick up the paper and it says ‘dead horses at Del Mar,’ people are going to say we got to close this place down,” Harper said.

For this reason, as well as the desire to protect horses and jockeys, Harper said that safety always comes before everything else.

“This is a sport [in which] horses do die … they die at the farm, everywhere else,” Harper said. “But nothing is being abused here and the racing-related injuries are certainly way, way, way down.”

Spriet said that veterinarians look at horses every morning before giving them “the green light” to train at Santa Anita.

“That’s something that has contributed to decreasing the number of breakdowns,” he said. “That’s something that has helped a lot. But then it doesn’t fix it all.”

At UC Davis, Symons said that most people were receptive to their research, but implementation was another hurdle. The CHRB must balance the needs of the industry with findings in research. They said that if regulations are too narrow, owners and trainers who do not wish to follow these rules will take their horses elsewhere to race.

“You have to strike a balance of ‘how do we how do we improve protections for racehorses in a way that is still palatable for people in the industry to participate?’” Symons said.

Jockey and veterinarian Peterson said that there is still a long way to go with research but believes the future of horse racing will be positive.

“Now you see that people are really searching for answers,” Peterson said.

One of those individuals, Spriet, has been on the quest to prevent catastrophic injury in horses ever since he came to UC Davis. Luckily, seeing the horse break down in France as a child was the only instance of catastrophic breakdown he directly witnessed in a race to this day.

Spriet said the PET scanner, which was worked on and tested at UC Davis, could change racing for the better in the future.

“I’m proud of it, and I think this is something that UC Davis can be proud of,” Spriet said.

Written by: Margo Rosenbaum — features@theaggie.org

Correction: The article previously stated that Blea was placed on administrative leave by UC Davis to prevent him from overseeing the necropsy of Medina Spirit. UC Davis placed Blea on administrative leave after the suspension of his medical license by the Veterinary Medical Board. The article has been updated to correct this factual inaccuracy.