UC Davis professors and alumnus explain the weather pattern hitting the Bay Area and Central Valley

By BRANDON NGUYEN — science@theaggie.org

To begin the new year, high-impact rainstorms have struck the northern coasts of California, leading to seemingly endless precipitation in the Bay Area and Central Valley. Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the Institute of Environment and Sustainability at UCLA and a UC Davis alum, highlighted the unanticipated intensity of the storm despite the weather forecasts on news media in a recent blog post.

“A strong storm on New Year’s eve brought very heavy 24-hr precipitation accumulations to a relatively narrow but highly populated swath of NorCal, from around San Francisco in the central Bay Area eastward to the Central Sierra foothills,” the blog read. “Here, some locations actually came close to (or even exceeded) all-time 24-hour precipitation records. This was pretty unexpected.”

Dr. Matthew Igel, an assistant adjunct professor in the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources at UC Davis, discussed the cause for the forecasted heavy rainfalls and flood warnings issued this past week.

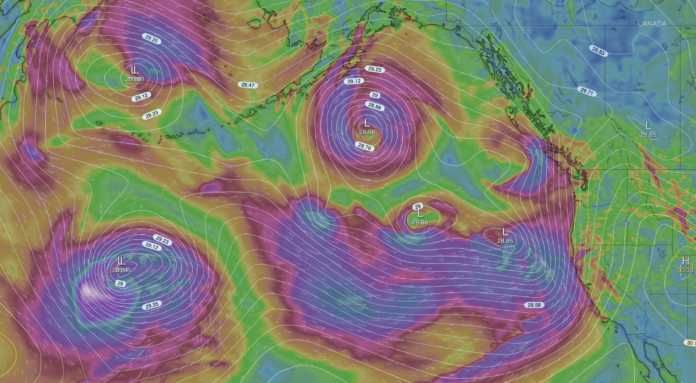

“The storm from a couple of days ago, forecasted for this past Wednesday [Jan. 4], was the one that was referred to as a ‘bomb cyclone’ in popular media,” Igel said. “This was, itself, a very strong storm, but I think the really interesting thing meteorologically right now is the fact that we’ve been getting repeated storms hitting California; the expectation is that we would be getting about three weeks of essentially continuous rain here in Northern California. And although we’ve had some exceptionally strong storms associated with this [rainfall], the story really is just the fact that it’s just been storm after storm after storm.”

A “Bomb cyclone,” also known as an extratropical storm, is a low-pressure system that intensifies rapidly, according to Igel. The center of the storm must meet a specific metric where its atmospheric pressure decreases at a specific rate to be classified as a “bomb cyclone,” and this type of storm typically occurs just outside of the tropics during the winter season.

Dr. Ian Faloona, an associate professor and bio-micrometerologist in the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources at UC Davis, explained how the bomb cyclone facilitated the heavy precipitation observed the past few days.

“What these cyclones, or these storm systems, are doing is they’re pulling air from the warm, humid tropics, where most of the water vapor on Earth lies,” Faloona said. “And so I think of it [the bomb cyclone] like a paddle wheel that’s coming along, and they [the storm systems] move generally from west to east because of how the winds generally move in our latitudes, and a lot of times they hit the coast, bank up along it and move poleward.”

The movement of water vapor in the atmosphere is also known as an “atmospheric river,” and the circular motion of winds created by the storm systems recently have helped direct these atmospheric rivers toward the coasts of Northern California. According to Igel, California’s unique topography also plays a role in the heavy precipitation observed. The mountain ranges like the Sierra Nevada mountains cool and condense the warm water vapor into rainfall due to the higher altitude of the landscape.

“Atmospheric rivers are essentially long regions of water vapor in the air,” Igel said. “They tend to be just above your head, in the first one mile of the atmosphere, so the term ‘Pineapple Express,’ specifically, is used to describe an atmospheric river that draws its moisture from the area around Hawaii. But an atmospheric river in general is just really tapping into all of that moisture in the warm, moist tropics and bringing it up here to the west coast of California, or really, the west coast of any continent.”

Both Faloona and Igel said that they could not pinpoint just one single causal factor as to why the severe weather patterns observed and forecasted are occurring.

“You see a lot of things that you’ve never seen before in weather, and it’s just kind of luck,” Igel said. “It’s tempting as a scientist to try to go back and really find root causes, and I’m sure that there will be some assessment in the coming years on this sequence of storms. It’s unlikely that the storms are directly due to climate change. At this point, it’s hard to describe a proximate cause other than that weather just happens, and sometimes it doesn’t happen. Winter storms are more intense to begin with, and we just happen to be at the peak intensity of storms at this time of year.”

Written by: Brandon Nguyen — science@theaggie.org