The co-founder and a club officer discuss the organization’s purpose

By SABRINA FIGUEROA— features@theaggie.org

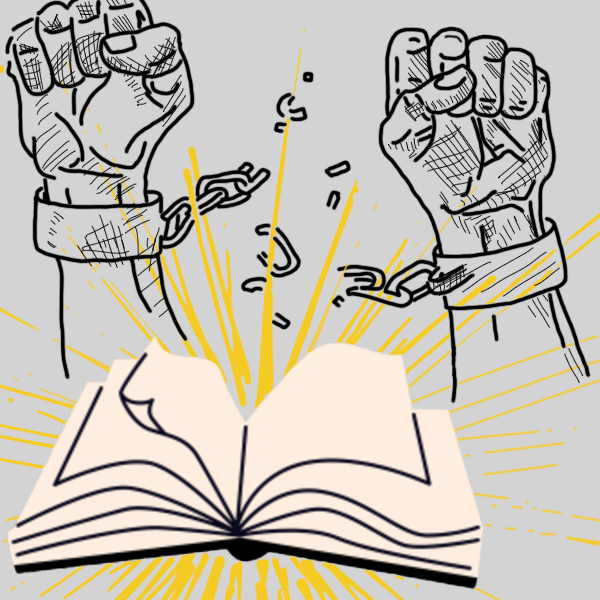

In the United States, 3 out of 5 inmates are considered illiterate, but only about 6 percent of inmates receive education to be able to read during their time in prison. That doesn’t stop them from wanting to learn and read about different topics they find interesting, nor does it stop non-prisoners from helping them achieve that goal.

Founded at UC Davis in 2017, Davis Books to Prisoners is an independent organization of many Books to Prisoners across the United States that are part of the larger Seattle-based nonprofit. The organization’s mission is to promote literacy and self-directed education for inmates, as well as “foster a love of reading behind bars, encourage the pursuit of knowledge and self-empowerment, and break the cycle of recidivism,” as stated on their website. From 2019 to 2022, they have sent over 2,000 books to incarcerated people located in various states.

“Our mission is kind of in the name, we’re just trying to get books to people in prison,” Colin Meinrath, co-founder of Davis Books for Prisoners, said. “We try to help disadvantaged prisoners achieve their own desired educational outcomes and help them do the kind of reading that they want to do which includes a wide range of [topics].”

The club communicates with prisoners all over the country primarily through mailed letters and books — so long as state law allows it. Some of the most popular states for the organization are California, Texas and Pennsylvania. Occasionally, they get letters and emails from people who aren’t incarcerated, but who request books on behalf of prisoners they know in either local or federal prisons.

The process of sending books can be seen in depth on the organization’s TikTok account. Every box of books and letters is sent through the United States Postal Service, so every donation of postage, paper and even envelopes is appreciated.

“[The sending process] is very old fashioned. Our mailbox is at the Center for Student Involvement, and they say that no other group gets as much mail as us. We do our best [to reply back], but it is hard because we aren’t a huge group,” Gisselle Garcia, an officer of Davis Books to Prisoners, said. “Sometimes we hold letter writing nights because, aside from just sending books and helping to promote education, we want to promote building community with people inside [of prisons].”

Handwritten letters sent to the organization from inmates are usually their requests for genres and topics they’d like to read about. Depending on the donation of books and money from community members or authors, Davis Books to Prisoners decides which books best fit an inmate’s request.

Some of the most popular genre requests are reference books, self-help, African-American studies, Latin-American studies, psychology, fiction and science fiction or fantasy books.

“Because we don’t get a great level of funding, we ask for general genres and try to fulfill [requests] that way instead of specific titles or authors,” Garcia said. “I think it’s interesting, though, because the range of requests is always fun to read. We get everything from picture books to things on gardening. I think someone also asked for books on ancient Mesopotamia, so super random, but there’s range.”

Meinrath also chimed in about book requests: “This I can say is true about other ‘Books to Prisons’ projects, too: the most commonly requested book is the dictionary, and that is because of their reading level and them seeking to improve their reading level.”

It is also important to note that these books are not just for one incarcerated person and that sometimes these ranges of books are shared with other inmates who also want to read and learn. These books help create a community inside of prisons just as well as they do outside of them.

“When [the inmates] say ‘We have a mini library’ or ‘We share books,’ we see that [the books we send] can touch other people’s lives,” Garcia said. “So, we have to remember that prisons have libraries, but what are the conditions of those libraries? What [reading] material do they really have in there? Sometimes it’s old [books], very limited or just very small. We seek to fill those gaps the best we can.”

Meinrath and Garcia also stated that the club sometimes takes phone calls with prisoners and that they are similar to the letters because they also contain requests for books, discussions of solidarity and community building, in addition to educational conversations.

“It’s a lot of community building, again, you know if sometimes [the inmate] is going through something, we’ll listen,” Garcia said. “We’ve built some lifelong friendships with people through [calling], so sometimes we’ll just be like ‘Hey, what’s going on?’ and things like that.”

Davis Books to Prisons is always looking for help, whether that is through volunteering, donating or even reading, learning and raising awareness about prison literacy — starting with understanding prisons in a broader sense.

“There are two organizations that can help inform people about prison literacy. One is called The Marshall Project, and they do work on prison reform generally. The other is called PEN America, and they do stuff around freedom of speech and censorship around writing, but they have taken an interest in prisons in the last few years,” Meinrath said.

UC Davis students, staff and other Davis community members with incarcerated loved ones are heavily encouraged to contact Davis Books to Prisons so that they can get connected with them. All information will be kept private and will not be disclosed unless otherwise instructed.

However, you don’t have to know someone in prison to get involved and contribute meaningful work. Volunteers with the organization recognize how important their work in the program is.

“Working alongside the Books to Prisons project has been so rewarding,” Aiden Willet, a third-year sustainable agriculture and food systems major, said. “Building connections with incarcerated community members reminds us that they cannot just be discarded by the system.”

The program’s efforts do not go unnoticed by the inmates, either. Their work is highly valued among their readers, and they continuously receive letters of gratitude that show how much of a difference they make in their lives: “I must express my gratitude to you and others who provide reading material for those incarcerated. As for one who didn’t know how to read [and] has fallen in love with reading, I thank you again.”

Written by: Sabrina Figueroa — features@theaggie.org