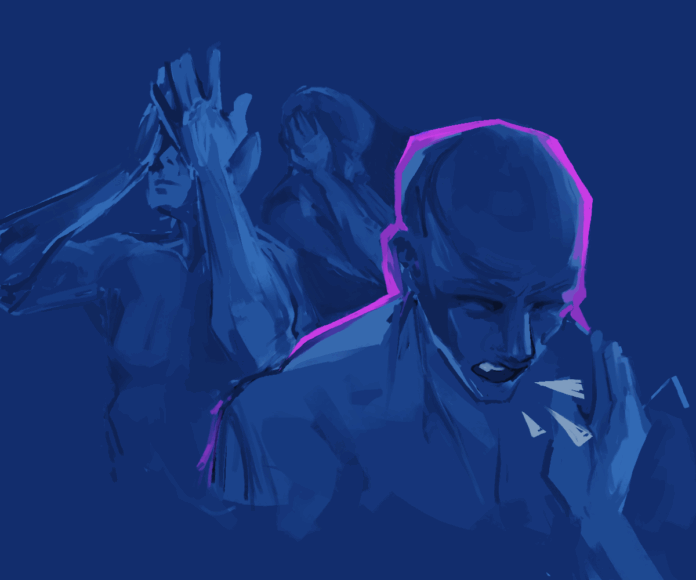

Affective polarization: an affliction with insufferable symptoms

By VIOLET ZANZOT— vmzanzot@ucdavis.edu

History will have its way with the affective polarization that exists in America today. Future textbooks will have headlines that read “The battle between the blue-haired and red-capped raged onward,” and Alligator Alcatraz will be memorialized similar to Manzanar. Much as we may have read about Ronald Reagan’s presidency and the civil rights movement, we can see plainly that we once again exist at a cultural and political inflection point — a moment in time that is producing a shift in our cultural norms.

Affective polarization — defined as “the tendency of Democrats and Republicans to dislike and distrust one another” — has been exacerbated by extremists, who create a feedback loop to push people further apart. The masses seem to be the fuel feeding the fire of the tension we’re seeing emerge between the political left and right: there is no question that there is partisan division in America today.

In essence, politicians and public figures are feeding off the existing social and political turmoil to gain popularity; they rally their supporters around collective animosity for the opposing side, tightening their allegiance to their party while decreasing their tolerance of the other.

Oftentimes, when we talk about the problems in our country today, speculatory commentary far outweighs self-reflection. How often do we look in the mirror and ask ourselves why we dislike or distrust people who think differently? How often do we assume we are right, without even considering what it even means to be right in the first place?

Researchers Jesse Graham, Brian Nosek and Jonathon Haidt studied the accuracy of how political liberals and conservatives stereotype one another. Their results revealed that the differences in how people think are exaggerated relative to the actual differences. It’s not that no differences exist, but rather that people have moved their perceptions of the “other” farther and farther away from their perceptions of themselves. Interestingly, they found that liberals were the least accurate in their stereotyping, while conservatives were more accurate and moderates were the most accurate. But, as a whole, participants demonstrated over-inflated in-group and out-group discrepancies.

When was the last time you asked someone who disagreed with you why they think that way, especially at a moral or ethical level? As a result of media sensationalism and the tendency for benefactors of polarization to prey on people, our planes of consciousness have been separated. If we could be more compassionate about why people think the way they do, perhaps we could reach more consensus on the grounds of “why,” even if we disagree on “what.” Our goals may be similar in spite of disagreements regarding how to approach them.

In the end, this is a war based on unfounded assumptions. It is not a substantiated distinction, it is a war of perception rather than material reality. Respectful politics have become old fashioned because we’ve allowed rivalry to take over. Maybe blaming the other side relieves us of any personal accountability, but this “othering” is not the smart nor the moral thing to do.

Written by: Violet Zanzot— vmzanzot@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.