The Internet is quick to extract political implications from album covers or lyrics — but how useful is this commentary?

By GEETIKA MAHAJAN — giamahajan@ucdavis.edu

There are more than enough reasons for the general public to dislike any celebrity. Like the rest of us, they are flawed people. But an endless well of money, power and attention has a tendency to amplify a universal, intrinsic predisposition to self-centeredness and narcissism. It’s hard to like someone when it feels like their whole life is being shoved into your face for the sole purpose of preserving their popularity, success and wealth.

That being said, there’s been a (very annoying) trend in recent discussions about celebrities, both on the Internet and outside of it. People seem to conflate their opinions of public figures with their own moral superiority; looking for reasons to justify their prejudice as something beyond simply not liking someone’s public persona. Unfortunately for everybody on the hate train for Taylor Swift, Sabrina Carpenter or Charli xcx (or whichever other famous woman the Internet has unanimously agreed that they’ve had enough of), collective acceptance of a sentiment doesn’t make it a fact.

Saying you dislike Taylor Swift because she’s a billionaire isn’t a valid critique if you’re not saying anything about Rihanna or Beyonce or Jay-Z, all three of which are Swift’s peers net-worth wise. Hating on Sabrina Carpenter because she “caters to the male gaze” is like criticizing Ford for catering to people who like to go off-roading or saying that Le Creuset promotes tradwifery. Like any other venture that generates revenue, celebrities are a brand. Criticizing them for how they present themselves is irrelevant; they do it because there’s a market that buys into this persona.

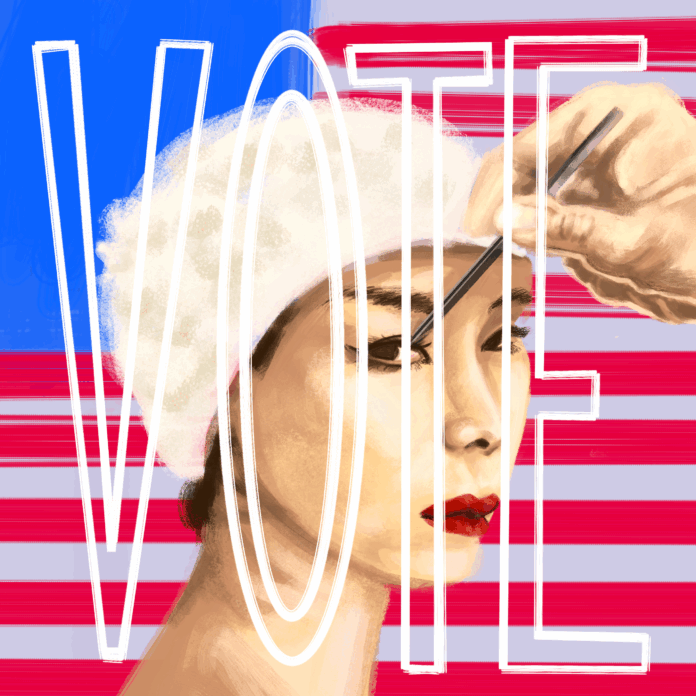

Taylor Swift’s net worth or Sabrina Carpenter’s album cover (both of which have been viciously torn apart by people online) aren’t reflections of them as individuals; they are consequences of how successful they are in catering to the demands of their audience. The self-righteous outrage over Carpenter’s “Man’s Best Friend” album cover being anti-feminist or how Swift isn’t utilizing her enormous wealth for one thing or another are symptoms of the characters they play to maintain their audience. Political critiques of celebrities are just as flimsy as those personas themselves — when you criticize a popstar you aren’t placing blame on a real person, you’re essentially chastising a facade.

Yet, there is a sociopolitical aspect to these hate trains. Accusing a celebrity of being the embodiment of capitalism or misogyny is less indicative of personal morality and more representative of how susceptible you are to mob mentality — you’re just jumping on the bandwagon. At the end of the day, expecting popstars to double time as political commentators is a very specific kind of brainrot that comes from spending all your time in pseudo-intellectual spaces online and zero time consuming or reading anything of actual intellect or substance. As long as Chris Brown is still selling out arenas, your criticisms of female celebrities are hollow.

This is not to say that celebrities need protection or require defending, but there are more useful and more valid political critiques to make when you criticize a larger industry or trend. If you want to hate on a singular person because you’ve cherry-picked facts about their life to fit a personal narrative about them, that’s fine — but keep your discourse on stan Twitter. Behaving as if criticisms of an album cover or lyric does the same work as criticizing a politician or bill is ultimately unproductive. Pop culture can be political, but it isn’t praxis — if you want to talk about politics, read the news, not your Twitter feed.

Written by: Geetika Mahajan — giamahajan@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.