Hyperindividualism is ruining your life

By ABHINAYA KASAGANI — akasagani@ucdavis.edu

I’ll admit that I have a tendency to retreat into my deliberately constrictive, shell-like enclosure in order to ward off the willies, the weepies or the like. I do, however, always manage to drag myself to “go to the party.” Let me explain.

Singer-songwriter Lucy Dacus shared this message with “Rolling Stone” in early October: “I have a friend who’s studying public health … and one of the things they learned was, like, ‘go to the party.’ You need to go to the party for your wellness.”

Sure, if you’re sick, you’re granted time off; but, ultimately, Dacus noted that “You can’t just self-care your way alone […] there’s a biological imperative to breathing each other’s air.”

Contemporary relationships fail to endure — far too often, they are undone by a general reluctance to “put in the work.” Our modes of connection — delivered through pixelated simulations of genuine care, wrapped in copper cuboids of despair — are hollow and gestural. We have begun to subscribe to friendship; opting out at our leisure and returning only when it’s convenient. While many blame technology (or find themselves a new scapegoat) for ruining the world as we know it, people have long since stopped prioritizing real life in favor of hyper-independence. We attempt to posture ourselves as good people, good friends even, but this verdict of goodness exclusively comes from ourselves.

The Internet has left us unwilling to admit that we care. There is a reluctance for earnestness; almost a distaste for it. One, instead, leverages boundary-setting as an excuse to avoid investing time and energy into others meaningfully, shielding an individual from responsibility or blame (and occasionally, even hurt). While apprehension toward power imbalances within relationships is understandable, the cult of hyperindividualism and emotional minimalism has bled us dry. Now more than ever, we retreat due to fear that our efforts will be unreciprocated. We have begun to conflate commitment with obligation. And, in doing so, we’ve lost sight of what we owe one another.

Friendships, unfortunately (or fortunately), continually demand intentional effort.

“All of us participate in the social contract every day through mutual obligations among our family, community, place of work, and fellow citizens,” according to Minouche Shafik’s “What We Owe Each Other.”

While Shafik notes how this participation has changed in recent years, she proposes “a more generous and inclusive society would also share more risks collectively […] a better social contract that recognizes our interdependencies, supports and invests more in each other, and expects more of individuals in return.”

This is not to say hypercollectivism is the answer. While it is simply false to claim we owe nothing to anyone, it is equally misguided to believe we owe everything to everyone. This generational impulse toward extremes has us buying into sentiments of guilt-based collectivism, which weaken personal boundaries and autonomy. Healthy interdependence requires you to recognize the extent to which we benefit from others, and to consider how we choose to give back.

This way of being is why we suffer — it’s why our political systems do too. Why do we find ourselves unable to collectively agree to vote for programs that would benefit everybody? We’ve been deeply trained to care only about ourselves and to believe that struggle is to be avoided at all costs. Ironically, struggle is where growth takes root and where community flourishes.

Dacus considers this in her argument.

“People just come home and stay in their houses,” Dacus said in her interview. “That’s great news for the government. We’re not showing up together or […] realizing how to organize without social media.”

She remains apprehensive about what this means for the future.

“[Once] they get in charge of that, you know, it’s harder to figure out how to get together,” Dacus said.

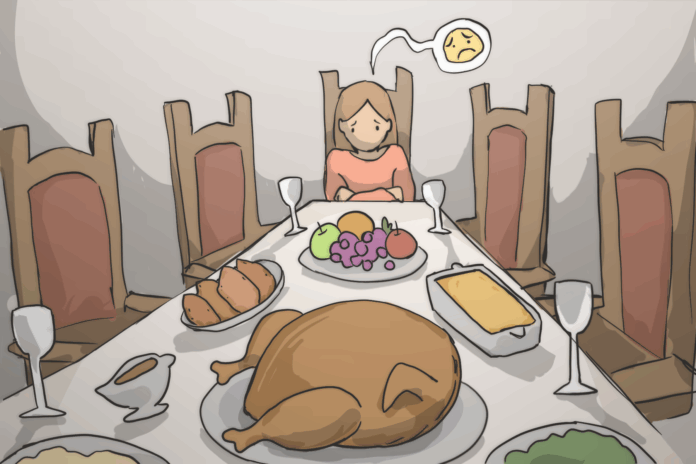

Right now is when it would benefit you to admit that you need others; working to take care of yourself doesn’t substitute that. So if your friend invites you to their birthday, go. Not showing up for your friends (on a Friday night of all nights) reflects a larger sociological inability to prioritize someone other than yourself. This epidemic of wanting constant comfort disguised as self-awareness is immature. Friendship requires sacrifice; community is built on sacrifice.

Let me be perfectly clear — I am not attempting to negate the value of a healthy boundary, but instead, imploring you to reevaluate the difference between setting a boundary and being lazy in your friendships. Community has fallen so low on our priority list that our allegiance to one another is flailing and so is our ability to experience our lives. Sometimes, it is perfectly necessary to sleep less than eight hours because you chose to go out. These boundaries you’ve drawn to excuse yourself from social obligations are unfortunately written in chalk; your task, should you choose to accept it, is to step outside the lines — or simply, step outside.

Written by: Abhinaya Kasagani— akasagani@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.