Regulatory silence shouldn’t be treated as a green light

By MILES BARRY —mabarry@ucdavis.edu

Kalshi is a prediction market organizing bets on nearly everything — from the date of Taylor Swift’s wedding to the number of deportations conducted in the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency.

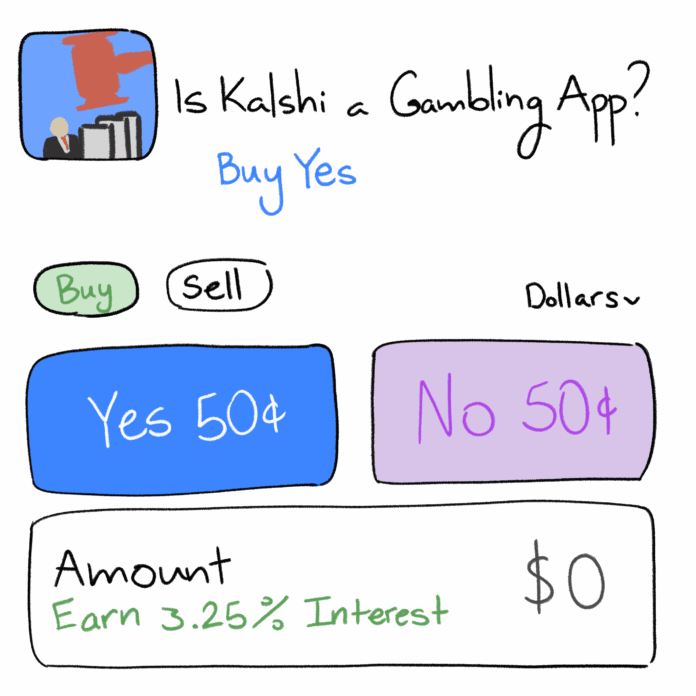

To facilitate these bets, Kalshi sells “event contracts” — essentially yes-or-no questions about future outcomes. Take “Will Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deport at least 500,000 people by the end of Trump’s first year?” Users can buy either side. If you purchase “Yes” for 25 cents and you’re right, you win 75 cents — the two sides always sum to a dollar. If one side receives more purchases, its price will increase with demand.

Prediction market fans claim that contract share prices can serve as approximations of an event’s likelihood; that 25 cents for “Yes” approximates a 25% chance that more than 500,000 people will be deported. Kalshi’s Chief Executive Officer, Tarek Mansour, even claimed in an interview that their markets are an “unbiased source of truth,” as they aggregate many people’s predictions about an event’s likelihood into one clear price. This marketing strategy seems like it’s working; Google Finance just inked a deal with Kalshi to integrate their contract prices into the website.

But most consumers aren’t very interested in Kalshi’s markets on whether Kamala Harris will say “Charlie Kirk” on the Rachel Maddow show (she didn’t). They’re interested in sports betting. By some estimates, 75-90% of Kalshi’s trading volume this year belongs to their markets on college and professional sports. Kalshi has essentially become an online sports betting platform, valued at $11 billion and operating in all 50 states — despite varying state laws concerning sports betting.

Several states (including Nevada, Maryland, New York, New Jersey and Ohio) and several Native American tribes have filed lawsuits against Kalshi, alleging that they’re operating an unlicensed sports wagering operation. Kalshi insists it’s not a gambling company — it’s a derivatives exchange, regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). But the CFTC doesn’t appear to be regulating their markets either.

The Commodities Exchange Act (CEA) allows the CFTC to prohibit the listing of swaps contracts based on “terrorism,” “assassination,” “war” or “gaming,” if they are found to be contrary to public interest. “Gaming” likely includes betting on sports, but the term was never defined precisely in the CEA. The Biden administration attempted to rectify this, but dropped its appeal in May 2025 after the change in administration. Based on this vacuum, the CFTC hasn’t prohibited Kalshi’s sports contracts. They also haven’t prohibited other contracts, like the aforementioned deportations one, that are likely against public interest — and distasteful at the very least.

Kalshi’s legal response is elegant in its circularity; it platforms the idea that only the CFTC can regulate swaps exchanges, and, since the CFTC hasn’t stopped their operations, therefore their contracts are legal. A federal judge in New Jersey bought this logic, writing that Kalshi’s sports contracts, “by their very existence,” constitute evidence of the CFTC’s “implicit decision to permit them.”

This argument could potentially hold if the CFTC could be trusted to act as a neutral referee. But Kalshi has established deep ties to both the CFTC and the Trump administration. Brian Quintez, who was Trump’s choice for CFTC chairman until his nomination was withdrawn in September, sits on Kalshi’s board of directors. Michael Selig, who was confirmed as permanent CFTC chair in December 2025, previously worked at a law firm representing Paradigm, one of Kalshi’s largest investors. While doing so, he co-wrote a letter in 2024 urging the CFTC to permit prediction market contracts — arguing that it’s “arbitrary and capricious” to ban sports event contracts. Caroline Pham, Trump’s choice for CFTC acting chair in January 2025, faced a 2022 ethics complaint for disclosing “highly confidential, nonpublic information” that benefitted Kalshi. Moreover, Donald Trump Jr. is a strategic advisor to Kalshi.

It could be argued that this is how expertise works: regulators understand derivatives because they’ve worked in the industry, at companies like Kalshi. But that’s harder to prove when Kalshi’s entire business model depends on the CFTC’s inaction.

So, who’s actually in charge here? Not Congress, which allows prohibition of “gaming” contracts but left the term undefined. Not the CFTC, now led by Kalshi’s allies. Not the states, which are being told federal law preempts their gambling regulations. And not the courts, which have treated regulatory inaction as regulatory approval. Until Congress defines what “gaming” means in federal commodities law — or the Supreme Court resolves the circuit split on federal preemption — Kalshi will continue operating in the gap between what regulators can do and what they’re willing to do.

Written by: Miles Barry—mabarry@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.