Scientists predict the expansion of the universe using Finsler gravity and highlight the limits of using just one model

By EMILIA ROSE — science@theaggie.org

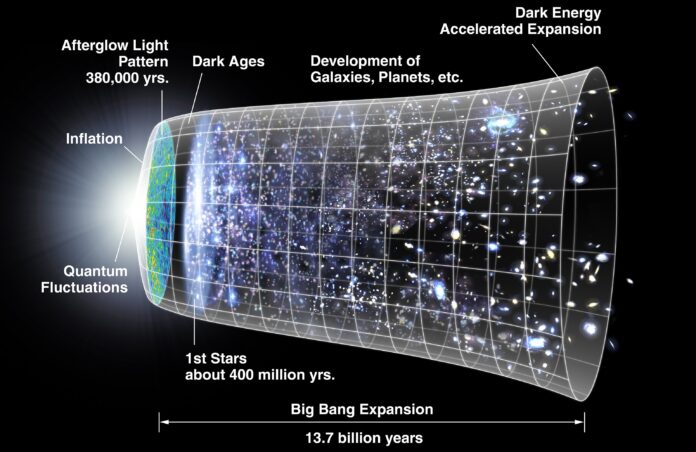

Where is the center of the universe? If we go back 13.8 billion years — over three times Earth’s age — current theories predict the universe existed as an infinitesimally small region containing everything we know.

Suddenly, this incredibly hot and dense region rapidly expanded, growing exponentially and cooling as energy converted into matter — the source of every object in the universe. This event was aptly called the Big Bang. Since then, the universe has cooled substantially, but has yet to cease its expansion.

Now, our intuition expects that when something blows up and expands, there must be a center that it all expands from. If you pump air into a balloon, then it’s natural to assume that all of the rubber lining expands outward from the center.

So, if it also expanded, where can we find the center of the universe? Surprisingly, the cosmos does not abide by this initial intuition. Imagine it like bread: If you heat the dough, every part expands away from every other part, not from the center. There is no need for a center.

The universe is remarkably similar in that it has no center. Space itself, the fabric of existence, is growing, and as we continue into the future, there will be more space between everything.

Interestingly, in 1998, two scientists, one of whom won the 2011 Nobel Prize in physics, inferred that the expansion of the universe was actually accelerating. Our current models suggest that the universe had two distinct phases of acceleration — one right after the Big Bang and one around 9 billion years later.

The more recent cause of acceleration suggested the existence of something that must be creating a negative pressure for space itself to expand. This theoretical source of acceleration is known today as dark energy.

Distinguished professor in the UC Davis Department of Physics and Astronomy and a pioneer in the field of cosmic acceleration, Dr. Andreas Albrecht, explained his interpretation of dark energy.

“Dark energy is something that can push matter apart,” Albrecht said. “The gravity we know every day pulls things together […] so we need something to represent the pushing apart. And we don’t really know what it is, but we call it dark energy.”

Dark energy is not a physical substance, as far as scientists know; you can’t run an engine or charge a flashlight with dark energy.

“Dark energy is usually a catch-all for whatever it is that you stick in [the equations],” Albrecht said. “It’s sort of this extra thing you need to put in to fit the data.”

Rather than discovering the existence of this mysterious substance, scientists found that the expansion of the universe was accelerating; the gravitational equations they had didn’t match this observation. To make up for it, scientists added a new mathematical term: a logical step for them to explain the cosmos.

However, a new paper from the University of Bremen suggested a different approach to explain the expansion of the cosmos. The team at the Center of Applied Space Technology and Microgravity (ZARM) at the University of Bremen used a geometric model called Finsler gravity, which is more often used to describe the gravitational behavior of gases in space. When the team at ZARM applied this to the large scale of the universe, they discovered that it predicted the observed acceleration without any mathematical term for dark energy needed.

So, which model is correct? Does dark energy truly exist, or is it an unnecessary mathematical term that we added?

The answer is that we don’t know. The universe runs on so many patterns, some of which are nearly impossible to predict: like asking where the center of it all lies. To make up for this uncertainty, we use mathematics and its predictable structure to explain the unexplainable in science.

Researchers across cosmology and physics tirelessly attempt to unite quantum mechanics and general relativity into one beautiful model. So far, we have not gotten the desired returns. Using one mathematical model to describe the behavior of the universe might be possible, or it might not be.

“Science succeeds, not because we know the right way forward, but because different people try different ways forward and eventually one of them works,” Albrecht said. “Where do we invest ourselves? Where do we invest our efforts?”

Regardless of whether we can find a unifying model — one that would explain not only the mystery of accelerated expansion but also many other mysteries in the cosmos — the different theories we create each move humanity forward, even by just a little.

Written by: Emilia Rose — science@theaggie.org