How accessible does science need to be?

By ABHINAYA KASAGANI — akasagani@ucdavis.edu

Let me start by saying Academia and I are not friends. Most days I don’t understand her, and she doesn’t understand me, but we keep in touch anyway. I get most of my information from her, and she’s usually credible. On the other hand, Academia annoys me deeply and is oftentimes unwelcoming, but she is perpetually trying to teach me something, for which I am grateful.

At dinner the other night with a friend of a friend, I was accused of being “out of touch” with the current state of access to academia — all because I concluded that it was not the density of research that intentionally kept people at arm’s length, but that it was the public’s unwillingness to approach a subject that didn’t appeal to them. The other party argued that a research paper’s failure to be instantly consumable by every person was the problem — noting that there exists both a moral and practical imperative that knowledge must be accessible to the public at all times.

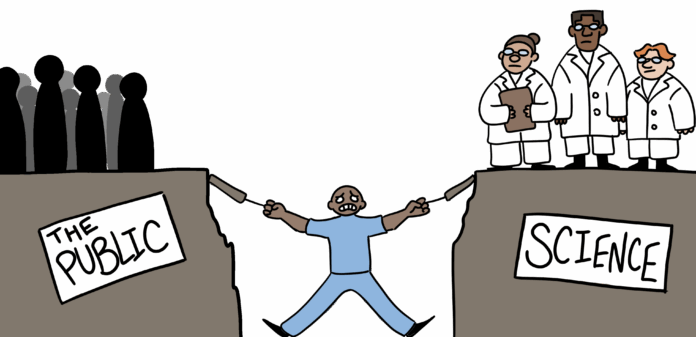

We failed to reach a shared consensus on whether or not it was the academic’s job to ensure the common person was kept in the conversation, which left me with the question: What is the attempted extent of a scientist’s allegiance to the public?

In the public imagination, information appears as if cloistered — an inaccessibility that is not incidental, but built into the systems of academia. Paywalls, technical jargon and talk of specialized methods function as barriers to accessibility, discouraging outsiders from participating. When direct access to researchers is denied, the public disregards nuance to back their biases or relies on intermediaries who might oversimplify or distort findings for their personal gain; when one has no access to the person who wrote the source and cannot verify what they intend to say, they fill in the gaps themselves.

The authority fallacy then results in the public’s acceptance of claims becoming hinged on trust in an authority figure, leaving them unable to weigh evidence themselves. Gatekeepers also advance their own agendas when they translate or filter research, realizing how easy it becomes to sway public opinion when the public lacks the necessary information to form their own beliefs. Some argue that researchers face cost and time constraints, and cannot be expected to distill all findings into layman terms for the sake of another’s convenience.

While the current social climate has made it evident that the public’s trust in science has begun to waver, most people still believe in the value and credibility of scientific research — it is scientists themselves whom they distrust. This often stems from their inability to engage with research or attempt to understand its methods — they demand certainty where none exists, often leading to a misrepresentation of scientific progress. They remain susceptible to misinformation by those who have been incentivized to spread it; paradoxically, this cannot be remedied if scientists spend their time and energies attempting to cater to the masses.

Still, if knowledge is power, and knowledge is continually restricted, then it becomes a failure of the research method to ensure that potency of that power is accessible by all.

Some solutions to mitigate this inaccessibility might include incentivizing public-facing materials (for instance, abstracts, summaries or data tied to publications in simpler language), more open peer-review and platforms for public commentary and requiring journals to reward open science practices like data sharing and explanations of methodology. Since transparency encourages accountability, it is easier to identify when error, bias and fraud are prevalent.

The responsibility of ensuring accuracy without compromising clarity and demystifying the research process doesn’t rest solely with researchers, nor entirely with mediators — it must be shared amongst educators too. They must teach citizens how to read science, understand bias and make inferences.

While I am still not sure I fully believe that publishing research necessitates the use of layman terms, I also agree that research mustn’t be walled off to those who want in. While a lack of transparency disenfranchises the public and fosters dependence on gatekeepers, a more literate, involved public is empowered to interrogate, challenge and participate in the public trust in science. Scientific literacy, in this way, ensures that citizens are not left behind as passive consumers — your brain, ultimately, is a muscle that must be deliberately exercised if you desire to not be excluded from academic conversations.

Written by: Abhinaya Kasagani— akasagani@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the

columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.