What is dark matter, how do we detect it and what does it mean for our understanding of the universe?

By EMILIA ROSE — science@theaggie.org

How much of the universe do we know about? Everything we can touch, see or even imagine — from the smallest particles to the largest stars — makes up only around 5% of our universe. Roughly 27% is something that we cannot even see: This substance is aptly named “dark matter.”

To further explore this mysterious substance, we must first evaluate what it means “to see.” Typically, when we see something, it is due to visible light bouncing off an object’s surface and entering our eyes. Some objects, like our sun, are even able to emit their own light because of the amount of energy they contain.

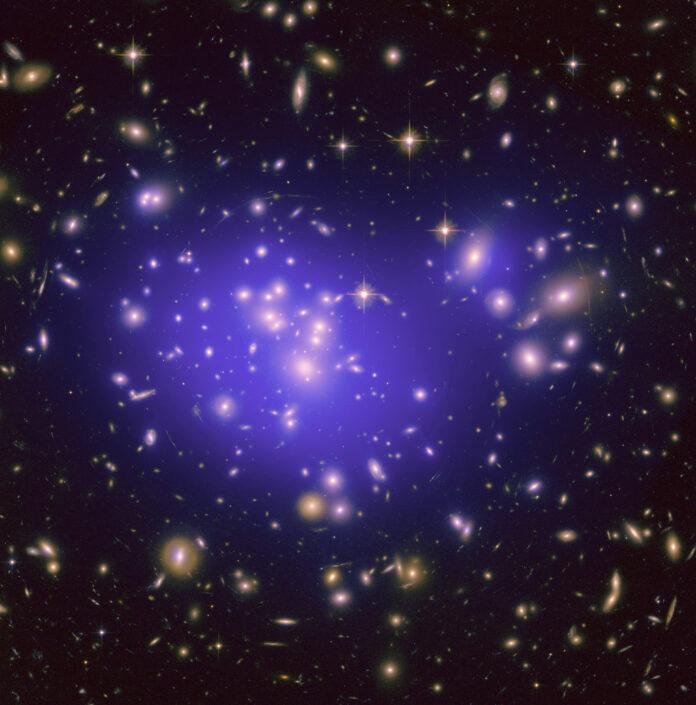

Now, what about dark matter? Can light reflect off it, or can it emit light itself? The answer is no. Dark matter is, quite literally, dark. In fact, scientists hypothesize that dark matter doesn’t interact with any form of light at all, making it invisible to the human eye. Given that dark matter is so elusive, and yet makes up so much of our universe, how do we know it’s there and how do we measure its existence in the wider cosmos? For scientists, one of the main forms of detecting dark matter is through gravitational waves.

Gravitational waves can be thought of as ripples in space-time caused by extreme cosmic events like black holes merging. Similar to when you throw a rock into a lake, these waves extend radially outwards.

Large observatories like the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) use machines with extremely long lasers to detect these ripples in space-time. When a gravitational wave passes through, the lasers distort in an incredibly small amount of distance (smaller than a proton), known as a strain. From this distortion, scientists can find the source of the wave and the dynamics of the gravitational event.

Yet when we look at this event, the gravitational effects we observe don’t match the amount of matter we see. From this, we can infer that there is some unaccounted mass altering the dynamics of the system. This is the implied existence of dark matter.

However, this method has a glaring weakness. Here on Earth, instruments are constantly affected by interference. We have air molecules throughout our atmosphere, minor shifts in the ground with tectonic activity and stray particles coming from outer space. Even with advanced filtering, these disturbances can disrupt readings.

Recently, a research team from the Universities of Birmingham and Sussex designed a new, much smaller detector that counteracts these problems, according to their newly published paper. Giovanni Barontini, a member of this team, commented on the mechanics of their proposed design.

“Due to [the detectors’] compact size, they are marginally sensitive to Newtonian and seismic noise, which are the main sources of noise for km-scale interferometers,” Barontini wrote in the paper.

An interferometer is an instrument that uses light or other waves to make extremely precise distance measurements. In other words, a “km-scale” interferometer would be something like LIGO. This new detector works roughly the same way LIGO does but on a much smaller scale, calibrated to detect gravitational waves at a frequency we have not been able to observe yet.

This is a groundbreaking achievement because it replaces massive, noise-prone machines with a compact device that can see in ranges we haven’t touched, while remaining more resistant to disruptions.

Centuries ago, humans started out using just their eyes to observe the cosmos. Now, we are working to observe the things our eyes cannot see. But, could there be a limit to how much our detectors can advance?

Matthew Citron, a high-energy physicist at UC Davis, explained his perspective on the matter.

“I think fundamentally, there are limits to how good a detector can be,” Citron said. “There are certain types of noise that are almost impossible to remove entirely. And, there are certain backgrounds that are impossible to remove as well.”

Jacob Steenis, a UC Davis graduate student in high-energy physics, commented on the idea of a theoretical limit.

“I do really admire how physicists often find clever ways to sidestep the impossible,” Steenis said. “I have the utmost confidence that — even where limits are found, theoretical or otherwise — physicists will continue to sidestep through indirect methods of measurement. To me, it really is amazing.”

Imagine two galaxies, both inconceivably massive, orbiting each other at incredible speeds. They circle each other over and over again until they become one. Their collisions are some of the most monumental interactions in our universe; yet when their effects reach us, their influence is almost undetectable. Like ripples fading as they spread across a pond, gravitational waves weaken as they travel vast distances.

Even with our most precise detectors, parts of our model of the universe still elude us. The existence of dark matter may one day be confidently confirmed, or it may remain something we can only infer through its effects.

Written by: Emilia Rose — science@theaggie.org