Suicide needs to be “discussed and addressed,” parents say

Content Warning: Suicide. Resources for 24/7 national and local crisis phone lines and text lines are listed at the bottom of this piece.

This article is the third in a three-part investigation by The California Aggie looking at suicide in the UC system. Parts one and two are available at theaggie.org.

What is a public university’s obligation to the well-being of its students? Several of the nation’s leading mental health experts, including from the National Institute of Mental Health, said, in actuality, there is none.

Universities “are not required to provide any care,” said Dr. Victor Schwartz, the chief medical officer of The Jed Foundation, a non-profit organization focused on suicide prevention for the nation’s teenaged and young adult population. “It doesn’t have to be that everything is provided on campus.”

Victor Ojakian is quick to dismiss this notion.

“The general premise of what an educational institution should be doing […] is graduating their students, and one of the ways you do that is by making sure that they have mental health treatment if they need it,” Ojakian said.

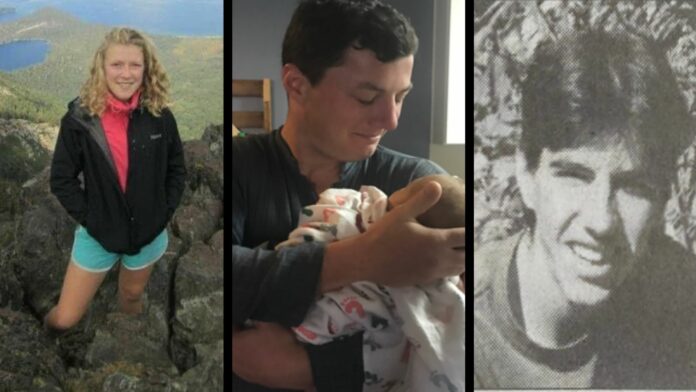

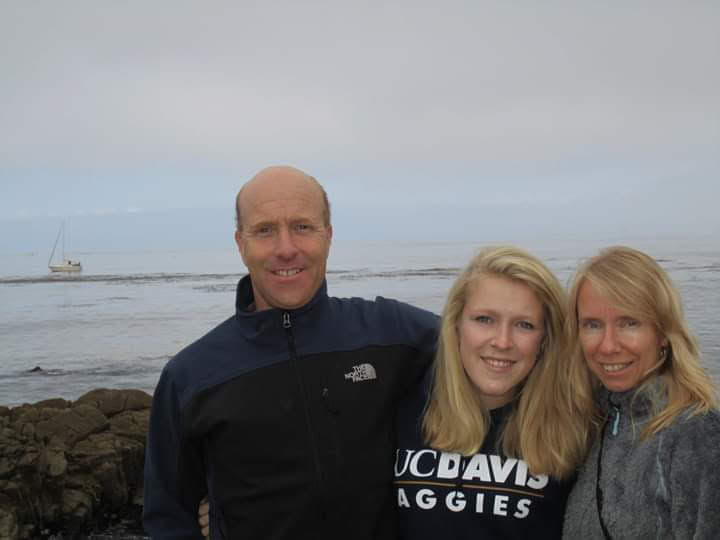

Ojakian’s son, Adam, died by suicide in December 2004 when he was a senior at UC Davis. Adam had not shown suicidal tendencies, and he was never diagnosed with a mental illness. His death is what is referred to as an “out-of-the-blue” suicide, Ojakian said.

“You’re subjected to someone you love taking their life unexpectedly,” Ojakian said. “And there is a level of trauma around that. I’m not even sure if I’m capable of explaining it.”

Later, in conversations with his son’s peers, he heard “what a wonderful guy” Adam was.

“I think one called him a ‘gentle giant,’” Ojakian said.

In retrospect, Ojakian suspects his son was struggling with major depression.

Adam’s death was also part of what is referred to as a suicide cluster. He was the fifth of six UC Davis students who died by suicide that year. A cluster, according to Ojakian, is not stopped “by doing nothing,” so it upset him that the university had not informed families of the situation.

At the time of Adam’s death, Ojakian said he “didn’t know four students had killed themselves prior to my son taking his life.” In his eyes, “it might have been helpful to know that.”

UC Santa Barbara, unlike UC Davis, notifies its campus community when a student dies. UC Davis students who served on the chancellor’s mental health care task force, convened in 2018, “were asking for more communication” from the university, and brought up examples of emails sent by UCSB to its student body upon a death in the campus community, said Margaret Walter, UC Davis’ executive director of Student Health and Counseling Services.

Currently, no changes have been made to UC Davis’ policy.

In the decade between 2008 and 2018, an estimated one to two UC Davis students died by suicide each year. This is the case for every year except three: An estimated four students died by suicide in 2011, an estimated three students died by suicide in 2012 and an estimated five students died by suicide in 2013, according to data collected by The California Aggie.

The UC does not require its campuses to collect suicide-related data, nor does there exist a “systemwide UC policy or standard on collecting suicide data,” according to Andrew Gordon, a spokesperson for the UC Office of the President (UCOP).

“There is no systemwide definiton of suicide nor policy thresholds at which suicides must be reported by a campus,” Gordon said via email. “Though campus counseling centers typically do collect this data and share with campus leadership locally.”

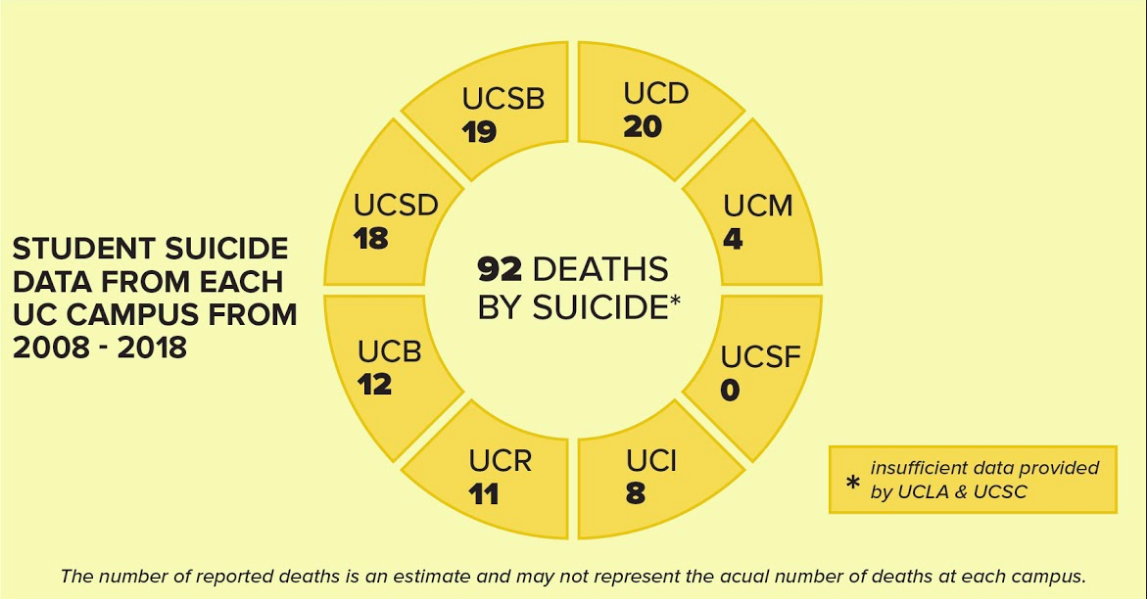

The Aggie submitted 20 California Public Records Act requests for the previous decade’s worth of student suicide statistics at each of the 10 UC campuses.

According to the responsive records, UC Davis, which saw 20 student deaths by suicide between 2008–2018, had the highest number of any UC campus. This number is based on deaths classified as a suicide by the county coroner, who then notified UC Davis Student Affairs. This data may not represent the actual number of student suicides at UC campuses over the previous decade. Because there is no system-wide definition or standard in use, it is difficult to accurately compare data on deaths by suicide across UC campuses.

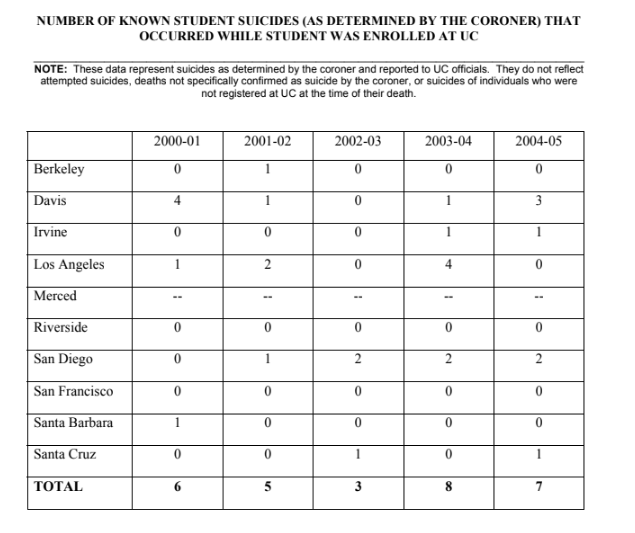

UC Davis also showed the highest number of student deaths by suicide of any other UC campus between the years 2000–2005, the period of time during which Adam died. UC Davis saw nine out of the UC system’s total 29 student deaths by suicide during this time period, according to the 2006 “Report of the University of California Student Mental Health Committee.”

In 2006, Ojakian was asked to testify at a U.S. congressional hearing aimed at updating the National Mental Health Act. He recalled that an aide for former Congressman Patrick Kennedy approached him and remarked on the UC’s report from that year.

“He said that they had been touring in California, and they’d just been visiting UC Davis and they understood that it had the highest number of suicides of any of the campuses,” Ojakian said. “That’s not something to be proud of. If you’re in that situation, you should be doing more.”

As far as he knows, Ojakian said his son had not sought out counseling services beforehand — but, as Ojakian noted, “I don’t know how he would have.” Over the past 15 years, the mental health resources offered by UC Davis have drastically changed. In 2004, the year Adam died, the CAPS budget “had been cut eight consecutive years; they were operating on a shoestring,” according to Ojakian.

In 2004, the year Adam died, the CAPS budget “had been cut eight consecutive years; they were operating on a shoestring,” according to Ojakian.

“We knew that students who were in need had no idea about what was available, what to do,” Ojakian said.

That’s when he and his wife, Mary, became advocates for student mental health.

For over a decade, the Ojakians’ advocacy work has led to tangible changes at UC Davis (additional student services); changes at UCOP (the creation of a Suicide Prevention Website and the Red Folder Initiative, a reference guide to mental health resources used by campuses both inside and outside the UC system); changes at the state level (Assembly Bill 89, which requires that all psychologists in the state receive training in suicide prevention) and even changes at the federal level.

Both Ojakian and Lomax worked on getting AB 89 passed for over five years — as Ojakian noted, if you do work in suicide prevention, “you have to be persistent.”

Described by others as a “fountain of information” on student mental health and suicide prevention, Ojakian repeatedly clarified that none of this advocacy work was done alone. He is also adamant about the fact that his advocacy work, which has saved lives, is not enough.

“We still think suicide is not something we can do anything about”

Since 1999, the U.S. has seen a 33% increase in its national suicide rate, and that rate is expected to rise amid the coronavirus pandemic. Yet, a “statistically strong and reliable method” to identify those at high-risk of suicide “remains elusive,” according to a 2016 study in the journal PLOS One.

Dr. Jane Pearson, the special advisor to the director on suicide research at the National Institute of Mental Health, said identifying factors that explain the upward trajectory of the nation’s suicide rate over the past decade is “the big question we would love to answer.”

“To say what one thing is contributing to suicide risks is really hard,” Pearson said. “The field is struggling right now […] to understand what’s going to be the most effective type of intervention.”

A key factor identified by several suicide prevention advocates is awareness. According to Craig Lomax, when a group of individuals understands foundational information about suicide and mental health, relevant stigmas and fears associated with seeking help are “reduced dramatically.”

In June of 2012, Lomax’s daughter, Linnea, died by suicide when she was a 19-year-old freshman at UC Davis.

“People described her as being extremely positive, extremely generous and just very interactive and encouraging,” Lomax said.

She was also diligent, thorough and a perfectionist, he said.

In May of 2012, Linnea was severely underweight and engaging in other physically destructive behaviors — “I just didn’t understand that it [was] the size of something much deeper going on,” Lomax said.

He remembers apologizing to Linnea’s roommate about the stress of the situation, and he recalls that “the roommate’s response was one of, ‘Oh yeah, well this kind of thing happens when you don’t know how to handle stress. I handle it just fine.’”

“She was clueless,” Lomax said. “I’m really not irritated, but that echoes my point of: What if everybody in the room understands the foundation of this? She might have been able to help surface Linnea’s understanding of what was going on. [Linnea] might have been able to get help earlier.”

On her 19th birthday, Lomax tried to talk Linnea out of taking her upcoming finals and coming home. UC Davis was immediately cooperative to the idea, but because Linnea was over 18, it was her decision to make. She was “absolutely certain” UC Davis was not going to let her return because she felt her grades were so poor, Lomax said, noting that she had a 3.83 GPA.

“Our rights are wonderful, […] however, when a mental illness comes in, it starts representing the body and that isn’t reflective of who that person is or their values,” Lomax said. “People start listening to the mental illness while the person is dying, and the mental illness wants to be destructive to the body.”

Soon after her birthday, Lomax found his daughter in a suicide attempt and took her to UC Davis’ Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS).

“The clinician looked at her and […] said, ‘Yeah, I don’t think that she’s going to commit suicide.’ I just came from a suicide attempt 30 minutes ago,” Lomax said. “The clinician was a little bit impatient because she had other things to do, but I pressed for a letter because in order to get her out of finals, we needed a letter.

“So we got that, but we didn’t get any other direction,” Lomax said. “We didn’t get any other help. We have no [idea] what to do, where to go, what to learn. Now that I know a lot about suicide prevention, [that was] completely incompetent and wasn’t adequate at all.”

“We didn’t get any other help. We have no [idea] what to do, where to go, what to learn. Now that I know a lot about suicide prevention, [that was] completely incompetent and wasn’t adequate at all.”

Lomax decided to write emails to a number of psychologists, one of whom recognized a dangerous combination in Linnea: that of suicidal ideations and perfectionist tendencies. The psychologist made an emergency appointment to see Linnea and recommended that she be admitted to an outpatient therapy center in Sacramento.

Linnea spent 10 days in a psychiatric hospital under a hold. On the eleventh day, she went to a voluntary outpatient program under the supervision of her hospital psychiatrist. On this day, she voluntarily left, three hours before her parents were scheduled to pick her up. She had not alerted anyone to her whereabouts.

“We were stupid, we didn’t think voluntary meant voluntary […] or I would have had a chair and waited and watched the building — that’s how concerned we were,” Lomax said.

Over the next 10 weeks, as Linnea’s story gained media coverage, over 1,300 people from Sacramento and the Lomax’s hometown of Placerville searched for her. Lomax said his family received over 300 phone calls reporting Linnea sightings, but only two of the 300 calls were actual sightings.

“Most parents can’t get it around their heads that their kid is suicidal, but even after you know that your kid is suicidal, it’s another thing to actually think they would do it,” Lomax said. “And that’s true of any human. We respect each other enough that we can’t fathom that that person that we know could actually do that, it just doesn’t make sense. So you have a hard time believing it. And we had 300 phone calls that said, ‘We’re seeing her in Sacramento.’ We would rather believe that.”

Ultimately, after a 10-week search, it was Linnea’s mother who found her body.

“It’s completely horrific and destroyed us in so many ways,” Lomax said. “It didn’t destroy us all the way, if I was still searching for my daughter, which I would be.”

The Lomaxes received hundreds of cards offering condolences for Linnea’s death, including one from UC Davis.

When Linnea died, Lomax said he was “totally uninformed about mental health and mental illness.” He has now educated himself and others on these topics.

“We do a lot of things nowadays to save a life,” Lomax said. “What degree will the campus go to save one of those lives? I suspect that they’d be willing to spend millions of dollars if they thought they could save a life. We still think suicide is not something we can do anything about.

How we talk about suicide

Patti Pape, an active member of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, is currently teaching classes aimed at de-stigmatizing mental illness. In these classes, she talks about suicide and addresses the “fact that bringing up suicide does not ‘plant a seed.’”

“It needs to be discussed and communicated,” Pape said.

Pape’s son, Eric, died by suicide in May of 2017 while attending UC Davis. Eric was a traveler, an anthropologist and someone who “worked hard” and “felt deeply,” Pape said. A psychology major, he entered UC Davis as a junior transfer and worked in a neuroscience lab.

According to Pape, Eric had not struggled with his mental health before transferring to UC Davis.

“The transition to Davis was more difficult than I had seen him experience before,” Pape said. “He had always had pretty stable relationships with friends and family, and not having that support system right at hand, right away, really took its toll on him.”

Eric began receiving support for anxiety and depression through drug therapy and through UC Davis counseling services. His first suicide attempt was in January of 2017, and he was checked into Sutter Davis Hospital and placed on a 72-hour 5150 hold. While there, an altercation occurred between Eric and a nurse at the hospital. After his release, and after he returned to school, Pape said Eric was doing better until he was charged with felony battery for the altercation.

“The trial was delayed and he felt more and more desperate,” Pape said. “He was still going and seeking services but he […] basically just decided there was no other way to solve the problems. His perception of himself was all based on what was going on with this trial and the outcome of that, because that was going to change his life irrevocably.”

In his last few weeks, Eric requested to see a specific UC Davis counselor, but there was a wait until he could see them. If Eric had been able to see the counselor, “I think that could have made a difference in the outcome,” Pape said. She believes the support UC Davis provided to Eric was “adequate,” but that “in a crisis, they let him down.”

After her son’s death, Pape received Eric’s diploma posthumously. She said she appreciated meeting the chancellor and being treated “in a nice way” by university officials, “but there was no acknowledgement of the fact that he killed himself.”

When a student dies by suicide, there is some level of fear held by a university that it will be blamed for the death, said Paul Gionfriddo, the president and CEO of Mental Health America.

Although UCOP does not require that campuses maintain student suicide statistics, Ojakian believes “they know who’s died on campus.”

“They try and hide it and mask it because they don’t want it reflecting on their service,” Ojakian said. “There’s a legitimate reason: They don’t want to create concern or consternation on a campus, but there’s also a level where they don’t want people to know students are dying on campus.

“My son died in the middle of December,” Ojakian said. “Then we got a call from the CAPS director — I think it was between Christmas and New Year’s. He’s calling for a reason. He knows my son is dead. They know. Regardless of what they say.”

In Ojakian’s mind, the UC president needs to be making sure that each campus has a plan and that these plans are being communicated between the campuses — “the fact of the matter is that the president’s office should be more involved.”

When it comes to work in suicide prevention, “you have to overcome things like being dismissed or avoiding dealing with suicide,” Ojakian said. “We think if we turn the other way, it won’t exist.”

But what happens when you lose someone to suicide?

“Other people talk with you, they ask you about what’s going on with their loved one or tell you about what happened to one of their children, so then you start seeing the bigger picture,” Ojakian said. “People started telling [me], ‘My son is at a community college and he has attempted to take his life.’ But it’s not just the campuses, it’s the whole culture that doesn’t want to talk about this. So, then you get to realize how big a problem that is. If you just sit back and do nothing, it’s not a solution.”

Ojakian’s home county of Santa Clara has a formalized suicide prevention plan, thanks to work done by Ojakian and others. His county is one of only seven out of the total 58 California counties that has a suicide prevention plan (Ojakian worked on a bill that would have required every California county to have a suicide prevention plan, but the bill was held by the appropriations committee without explanation).

Santa Clara has the lowest suicide rate in the state. Whereas the state of California has seen an increase in its suicide rates over the past several years, Santa Clara has seen a decrease from 150 down to the low 130s.

“I’m not a clinician, but it doesn’t prevent us from doing something,” Ojakian said. “I’ve educated myself on this topic, because my end goal is to save lives. In a sense, I’d rather not have people call me. I’d rather know that everyone’s loved one is safe and/or getting help because they need it.”

Suicide prevention at UC Davis

When the head of a university’s counseling department is asked about the work they do related to suicide prevention, they will say that all of their work is, in some form, related to it.

“All the work we were doing was effectively an attempt at suicide prevention in the same way providing medical care working in hospitals is working death prevention,” Schwartz, who was also the former medical director at New York University’s counseling services and current chief medical officer of The Jed Foundation, said.

The current work related to suicide prevention undertaken by UC Davis is vast and varied. After noticing an uptick in student suicides, UC Davis officials began a multi-year process guided and supported by The Jed Foundation. The process has consisted of the foundation providing the university with feedback aimed at improving its mental health care and suicide prevention efforts.

When schools provide more of these types of services, “suicide rates go down,” Schwartz said.

As part of a recommendation by the foundation, UC Davis has recently created and implemented a set of postvention guidelines used by the university in its response to traumatic events, including suicides. The guide is meant to ensure “a rapid and adaptable response aimed at preventing the trauma from growing,” according to the UC Davis website.

“Last year was about improving access,” Walter said. “We’re trying to open up the avenues where students can get support.”

And because universities provide some form of reliable community support, there is reason to believe that college is a safer place to be for individuals with mental health issues. In fact, the “actual rate of suicide is lower among college students than non-college-attending 18- to 25-year-olds,” Schwartz said.

Ojakian and other advocates, however, see college campuses as having a “captive audience” and, thus, an opportunity to reach out to students and let them know that “there are alternatives to taking your life.” There is a shared belief held by Ojakian, Lomax and Pape that universities can and should be doing everything in their power to prevent suicides from occurring.

“As parents, we send our children to an institution of higher learning assuming that these places are enlightened and open to research-based changes, and then when they seem to disregard that responsibility it’s disheartening,” Pape said. “What is the focus of the UC system? Is it research? Is it fundraising? Or is it our undergraduates and graduate students who need to get an education in a nurturing environment?”

This past May 4 marked the second anniversary of Eric’s death. In a recent email, Pape talked about the feelings that the anniversary prompted.

“Everyday is a bit easier to recognize the reality of our loss, but it certainly doesn’t keep us from missing his presence and wondering how he would be reacting to the craziness our world is in with this pandemic,” Pape said. “We all agree he probably would have backpacked up into the mountains and waited it out.”

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, Chancellor Gary May has made it a point to highlight the mental health resources available to students. Those resources, as they appear on the SHCS website, include the following:

- Mental health visits: Counseling Services are available by phone or via secure video conferencing. Schedule an appointment through the Health-e-Messaging portal or by calling 530-752-0871. All Mental Health Crisis Consultation Services are offered via phone consultation or secure video conferencing. Call 530-752-0871 to access these services.

- COVID-19 Mental Health Resource Flyer (pdf download)

- LiveHealth Online: Have secure, online video visits with licensed mental health professionals and primary care providers; no referral is needed.

- Therapy Assistance Online: Use interactive tools and self-care exercises for mental health concerns.

The number for the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is (800) 273-8255; the number for the 24/7 Crisis Text Line is 741741; the number to speak with a trained counselor through The Trevor Project, available 24/7, is 1-866-488-7386 and the number for Yolo County’s 24-hour crisis line is (530) 756-5000 for Davis callers.

Written by: Hannah Holzer — campus@theaggie.org

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article stated that Linnea Lomax voluntarily left a Sacramento hospital. This has been clarified to reflect that Lomax spent 10 days in a psychiatric hospital and was then transferred to a voluntary outpatient program. It was this program that she voluntary left. The article has been updated to reflect these details. The Aggie regrets the error.