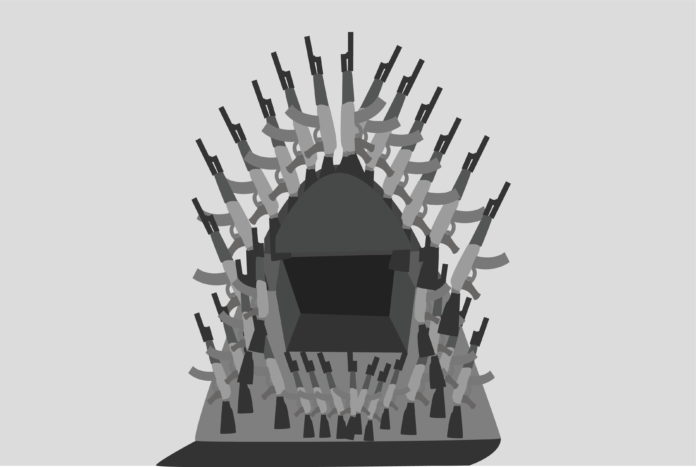

Why does violence hold such mass-market appeal in our entertainment culture?

A few weeks ago, I replayed one of my favorite games of all time: “Uncharted 2.” It’s the game that fully introduced me to what video games could be –– a masterful way to tell stories in a fun and engaging way. I tried to keep in mind an often-heard criticism about the main protagonist: Nathan Drake is essentially a mass murderer, killing hundreds of enemies throughout the game. “It’s just a video game,” I would tell myself. But is that a valid excuse?

Throughout my playthrough, my admiration for the game remained unchanged — it was as enjoyable as it was before. But, a constant question remained: Why is violence the default gameplay objective in the industry? And why does violence hold such a large stake in our mass media culture and entertainment as a whole?

A quick Google search of violence in video games will lead you to an unending debate over whether or not violent video games cause violent behavior in young people. However, what I find more interesting is the overwhelming frequency of violence (guns, brawling, violent acts) as the default for gameplay. Why are developers and gamers so comfortable with killing?

The 10 best-selling games of last year reveal how dominant violent games are in the video game market. Eight of the top 10 games from 2018 featured violence as the main form of gameplay. This phenomenon isn’t just limited to video games — eight of the top 10 movies from 2018 featured violence as well. But it certainly feels more prevalent in the interactive experience that games provide.

Mowing down hundreds of enemies seems routine for the majority of video games. And sure, most enemies will kill you if you don’t kill them first — that’s the conflict game designers always give us. But that’s part of the issue, too. Why are game worlds designed so that killing is often the core mechanic? Many older games like “Tetris” and “Pong” featured zero violence. But, as graphics and gameplay capabilities advanced, games became more violent — or at least seem more graphic in comparison. As games like “Contra,” “Mortal Kombat” and “Call of Duty” have found success, the default mode of conflict has turned to killing.

Where does this obsession and attraction to violence come from? Is violence just the easiest way to create conflict? Is it all necessary? Do we as consumers really demand this much violence?

Maybe the answer lies in the success of non-violent games. Independent games like “Journey,” “Gone Home” and “The Witness” tell compelling stories with engaging game mechanics and without violence. AAA developers — the big-budget industry giants like Ubisoft and EA — seem hesitant to breach into this genre of gameplay on a large scale. Yet these non-violent, independent games found success on a smaller level both critically and financially.

Ultimately, in all forms of entertainment, violence is used to build up adrenaline, conflict and consequence. The ultimate consequence in these games is death. But the infliction of pain in digital death is so often lost in our depictions of violence. Violence is simply the easiest way to create conflict — it’s immediately recognizable. Kill a hundred enemies in a video game or in a “John Wick” killing spree, and they will simply slump to the floor.

We need to reassess what our entertainment-obsessed culture favors and why we watch and play the games we do. I love “Game of Thrones” and “Star Wars” as much as anyone, but I have to ask myself why violence is such an attraction. Certainly there’s a space for it, and many depictions of violence are handled appropriately. What I think about video games time and time again, however, is whether this frequency of violence is really necessary.

When I play games, I usually play them for the story they tell and the characters I meet. My favorite part about games is not the hundreds of people I have to kill in between cutscenes — it’s the cutscenes themselves, simply because they advance the game’s plot more directly.

Reflecting upon the overwhelming frequency of violence in video games, I find myself wanting new experiences that aren’t fixated on running-and-gunning. Diversifying the palate of available AAA games with more varied experiences of gameplay and story can only be good for the industry and for gamers. Often the violent AAA games are so big, violent and boisterous that it’s hard for new gamers to enjoy those experiences, whereas independent games like “Journey” and “Gone Home” offer remarkable, quality experiences at a lower cost for developers and gamers.

Written by: Calvin Coffee — cscoffee@ucdavis.edu

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by individual columnists belong to the columnists alone and do not necessarily indicate the views and opinions held by The California Aggie.