It has been over 100 years since the world experienced the devastating 1918 pandemic, and history seems to be repeating itself, according to UC Davis professors

Before COVID-19, it had been over 100 years since the world experienced the H1N1 influenza pandemic, more commonly known as the Spanish flu. The flu hit right at the end of World War I and continued in waves into the 1920s, and the virus was believed to have far more fatalities than the war. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Spanish flu caused 50 million deaths worldwide.

Despite its name, the Spanish flu was thought to have originated from the U.S.. Spain remained a neutral country during the war, and the national newspaper in Spain was one of the only papers that reported about the virus, leading to the name ‘Spanish flu.’

COVID-19 parallels the Spanish flu in many ways. Pictures of people wearing masks in 1918 and anti-mask protests have been circulating around social media as of late. Last April, The California Aggie completed its digitalization of its archives since its foundation in 1915. The archival records show articles written by Davis students in 1918, when the Spanish flu pandemic was at its peak.

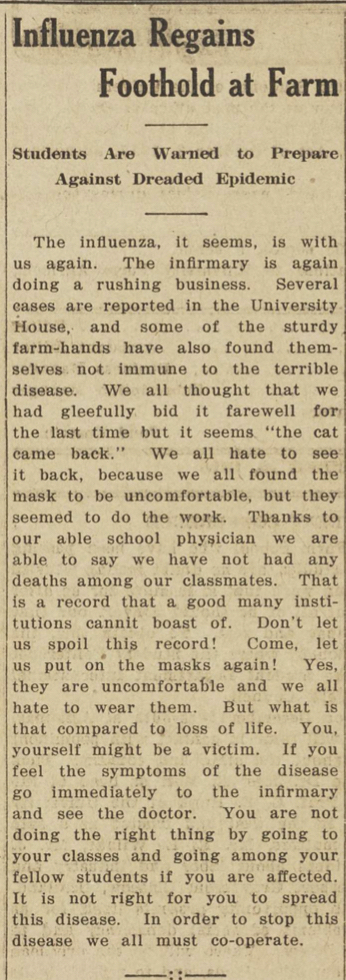

“Influenza Regains Foothold at Farm, Students Are Warned to Prepare Against Dreaded Epidemic

The influenza, it seems, is with us again. The infirmary is again doing a rushing business. Several cases are reported in the University House, and some of the sturdy farm-hands have also found themselves not immune to the terrible disease. We all thought that we had gleefully bid it farewell for the last time but it seems ‘the cat came back.’ We all hate to see it back, because we all found the mask to be uncomfortable, but they seemed to do the work. Thanks to our able school physician we are able to say we have not had any deaths among our classmates. That is a record that a good many institutions cannit boast of. Don’t let us spoil this record! Come, let us put on the masks again! Yes, they are uncomfortable and we all hate to wear them. But what is that compared to loss of life. You, yourself might be a victim. If you feel the symptoms of the disease go immediately to the infirmary and see the doctor. You are not doing the right thing by going to your classes and going among your fellow students if you are affected. It is not right for you to spread this disease. In order to stop this disease we all must co-operate.”

Dr. Sarah Dye, an assistant professor of global disease biology, gave a brief overview on the scientific similarities and differences between the two diseases.

“Scientifically they’re completely different viruses,” Dye said. “They are in two totally different taxonomic groups, although they are both respiratory viruses, have similar symptomatology and both originated from animals and migrated to humans. But they aren’t closely related.”

Another key difference between the two viruses is the age group they affect the most. According to Dr. Edward Dickinson, a professor of world history and the history of imperialism, the Spanish flu mainly targeted men ages 20-40 whereas COVID-19 is believed to most severely impact individuals ages 65 and older.

Dr. Neil McRoberts, a professor of plant pathology, studies the epidemiology of vectored plant diseases and the impact of the spread of diseases throughout populations. According to McRoberts, COVID-19 is believed to be much more deadly.

“Even though there were 40 million people who died from the Spanish flu, COVID-19 is known to be much more infectious, so you are more likely to catch it compared to the flu,” McRoberts said. “The fatality rate for COVID-19 is much higher compared to influenza and the reason that there were significantly more people who died from the Spanish flu is largely due to the fact that we were not scientifically advanced enough to treat influenza back then.”

Research has shown that the 1918 influenza strain was highly virulent and transmissible. According to Johan Leaveau, a professor of plant pathology and disease and society, a combination of low quality medical care, poor hygiene and lack of medical technological advancements contributed to the higher numbers of deaths for the Spanish flu. By the end of 1919 there were believed to be 50 million lives taken by influenza. So far COVID-19 has taken about 1.5 million lives.

In early March of 2020, California was the first state to issue a stay-at-home order. Dye discussed how the concept of quarantining was implemented during the Spanish flu as well.

“From what I understand about the 1918 pandemic, there were no strict lockdowns like we have now,” Dye said. “The response from health officials was like localized patchwork, meaning that the federal government didn’t have a lot of influence on how the 1918 pandemic was controlled. Local responses played a much stronger role, which is similar to what we are seeing with COVID-19 with states issuing different policies about quarantining.”

According to Dye, another reason that stay-at-home orders were not mandated during the 1918 pandemic was because a majority of the working class held jobs that required in-person manual labor.

“A strict quarantine would have been more difficult to implement without completely shutting down the economy in 1918 because we didn’t have things like Zoom,” Dye said. “If people fell sick and stopped going to work, they stopped earning money and that would have made it difficult for them to support themselves and their families.”

Leaveau further explains how the lifestyles of people during the pandemic hasn’t changed much over the past hundred years.

“What strikes me the most are not so much the differences, but the similarities,” Leaveau said. “People were asked, as they are now, to stay home, socially distance and wear masks; shops closed and went under; people got tired of the pandemic and of the mandates imposed by public health officials and let down their guard, which resulted in additional outbreaks and preventable deaths. It all sounds very familiar.”

The public responses to the two pandemics have been significantly different in terms of provided care, Dye explained, largely due to the fact that the majority of the population was not treated in hospitals during the Spanish flu.

“I think the fear was a bit more tangible in the 1918 pandemic,” Dye said. “With COVID-19, if someone gets really ill, they go to the hospital. You aren’t allowed to visit them, so you don’t really see the gruesomeness firsthand unless you are a healthcare worker. With the 1918 flu, those who were sick were most likely put on bed rest in their homes instead of being treated at hospitals, and oftentimes they would see people on the streets getting very sick and dying.”

Similar to the COVID-19 pandemic, the health restrictions in 1918 like wearing a mask caused resistance, Dye said.

“Interestingly, there were people that protested wearing masks back in 1918 and there was even a whole anti-mask league that was formed in San Francisco with people claiming that masks made them hot and uncomfortable like they do now,” Dye said. “So I do think that there is a lot of similarity between the two pandemics in terms of the public responses [to health directives].”

There have been a lot of technological advancements in the past century, some of which have helped healthcare officials fight COVID-19. Advancement in social media and news coverage, however, has been detrimental to flattening the curve, according to Dickinson.

“I think social media has clearly had a very negative impact [on COVID-19],” Dickinson said. “There are bizarre theories floating around—about this being a fake epidemic—that are given currency by the fact that anyone can post whatever they want to. The amount of disinformation that is being produced is incredible, and there wasn’t the capacity to generate nonsense in 1918.”

Dye believes, however, that the spread of false information was prevalent even in 1918, and countries went as far as censoring information about the virus to maintain wartime optimism.

“There was a lot of disinformation even back in 1918, but not [to] the extent that it spreads now,” Dye said. “The pandemic was going on during World War I and so countries that were actively fighting in the war wanted to suppress reports of how bad the influenza pandemic was to keep up morale for the war.”

McRoberts explained how through social media and the news coverage, the pandemic has become more of a political issue than a global health crisis.

“Social media is dangerous in a situation like this,” McRoberts said. “The ideas of social distancing and masks have become a political issue and the spread of misinformation about the importance of these things has become essentially uncontrollable. While we are battling the COVID-19 pandemic, we seem to also be fighting the misinformation epidemic, which was not as significant or even possible in 1918.”

Dye noted that in addition to social media, a lack of a unified message about the response to the virus in some countries has played a role in the spread of COVID-19 compared to the Spanish flu.

“I do think that back then, staying home when you were sick and taking the proper precautions to stay safe were considered to be more a patriotic duty,” Dye said. “By staying home you would help win the war and [it would be] for the good of your country. And we’ve only heard that message from our government recently, from President-elect Joe Biden.”

McRoberts noted that in addition to the increased patriotism in 1918, the growing rate of social individuality has been a contributing factor in the countries with the highest rate of infections.

“Back then, around the world there was a stronger social fabric,” McRoberts said. “People would conform to what was expected of them, and they generally had a stronger tendency to follow instructions, compared to what we see now.”

In the early 2000’s the idea of One Health was introduced at the CDC. The goal of One Health is to have a method of local, national and global collaboration to achieve optimal health care for people around the world. Dye explained the role of One Health in the fight against COVID-19.

“We have scientists now who have been studying diseases like this and other animals for potential viruses,” Dye said. “To a degree, we had some knowledge about coronaviruses and how they worked, so we had scientists ready to hit the ground running because they were already studying zoonotic disease that had the potential to become catastrophic.”

It has been over a century since we last experienced a pandemic, and Dye shed some light on what she thinks we as a society have learned from these health crises.

“I think one of the biggest lessons that we learned from the 1918 pandemic is the importance of getting on top of it quickly,” Dye said. “Unfortunately, I don’t know if that has even really been implemented now with COVID-19. Governments didn’t really start taking action right away, so the Spanish flu was able to spread fast. Once it starts to spread it’s much harder to control it, which is what we also saw happen with COVID-19.”

Dye also emphasized the importance of having government and health care organizations that are able to gain and maintain the trust of the public.

“Organizations and governments in charge need to be transparent and openly communicate and give out reliable information,” Dye said. “Right now there is so much controversy because the information that was given to the public kept changing. And unfortunately, that’s just the way that science works; you learn and then you revise your hypothesis and then you revise your recommendations. But not everyone understands how the scientific method works, to them it might seem like no one knows that they are talking about.”

According to Dr. Joanne Emerson, an assistant professor of plant pathology, a sense of unity is important to combat a pandemic.

“What we can learn from the current pandemic and the 1918 pandemic is the importance of a coordinated body.” Emerson said. “As a society we need to do a better job of outlining how our personal actions can impact the welfare of others. This issue is not one dimensional and these are events that are going to impact our future generation, and we need to keep that in mind.”

Written by: Sneha Ramachandran — features@theaggie.org

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly referred to the COVID-19 pandemic as the first pandemic since 1918. The article has been updated to correct this error.