John O’Brien visits Davis Senior High School to discuss his lifelong contributions to activist causes

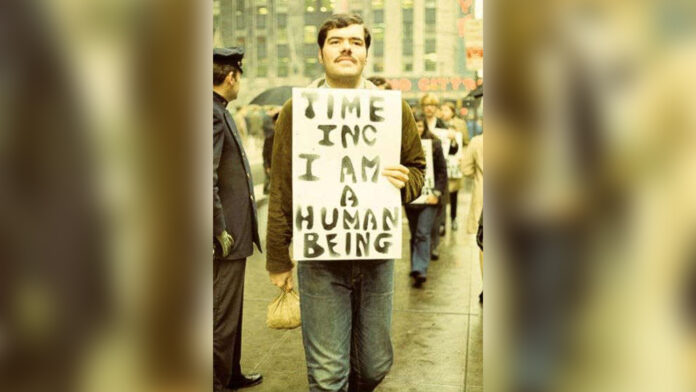

Walking into the Davis High School Brunelle Theater on Feb. 18, Davis and UC Davis community members would have first noticed a large photograph projected centerstage. In the photo, a young mustached man standing outside the Time Inc. building in New York looks slightly above the camera. He holds a sign that reads, “I am a human being,” a reference to the slogan “I am a man,” from a sanitation workers’ strike that occurred the previous year. Behind him are the blurred outlines of many other protestors holding similar signs, responding to the statement in Time Magazine that people who identified as gay were subhuman.

The man in the photograph is John O’Brien in 1960, a self-declared “troublemaker” based on his participation in the gay rights, civil rights and women’s rights activist movements and participation in the Stonewall riots. O’Brien became involved in activism from a young age, joining the NAACP at age 13. In the photo, O’Brien holds the poster in one hand and a bag in the other.

“I’m holding a little bag in that picture because it’s got a bunch of anti-war buttons, and that night I was going to Penn Station to get on the train to head for the anti-war demonstrations taking place in Washington D.C.,” O’Brien said. “I learned how to multitask, and that’s what I was doing for that and many other events.”

June 28, 1969

The Stonewall uprising began on the morning of June 28 when New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York. The event set off a six-day period of protests. O’Brien said he didn’t plan to participate in Stonewall.

“I was simply down the street […] with a bunch of political people having a discussion, and the police cars came […] and people were running away from that street,” O’Brien said. “When I got there, people were throwing pebbles and cans at the police.”

After O’Brien reached the scene, he contributed to the protest by lifting a parking meter alongside a few other men and used it to barricade the police inside the bar. As the protests went on, O’Brien and other protesters evaded the police until the situation took a turn for the worse three nights later.

“Then the police got really brutal,” O’Brien said. “They clubbed and hurt a lot of people. They were really bloodied, and a couple [suffered] lifetime injuries.”

For O’Brien and other protestors, the great significance of the Stonewall Inn in their community is what fueled the riots.

“Particularly for poor kids like me, we didn’t have any money to go to any elegant places,” O’Brien said. “[Stonewall] was our only place, and these kids were willing to stand up and fight against the police. It’s quite remarkable.”

Pride: 1970 vs. today

On the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots, O’Brien helped organize the first gay pride parade. Fifty years ago, he did not anticipate the expansion of pride into the national celebratory event that it is for the LGBTQ community today.

“I had no idea what this would lead to,” O’Brien said. “We didn’t think we were going to get to the end of the march.”

According to O’Brien, the police tried to stop the march with barricades.

“We had to […] run past the cops, and then we had to push them twice, physically, to get them to move the barriers,” O’Brien said.

For O’Brien, the commercialization of pride is disappointing, especially because many of the corporations that participate in pride today historically discriminated against gay people.

“We see AT&T and IBM in [the march],” O’Brien said. “The reality is that, in 1969, when we did Stonewall, AT&T and IBM actively fired people for being gay.”

In O’Brien’s words, the parade no longer reflects the original purpose of the movement. He hopes that young people will carry on the spirit of protest of the 1970s.

“Our movement has to go beyond just celebrations,” O’Brien said. “About building [a] community that cares for all.”

Supporting “our sisters”

For O’Brien, LGBT activism is interlinked with other movements.

“Racism [is] an LGBT issue,” O’Brien said. “If we’re going to have a community, a real community, if we’re going to stand up for ourselves, […] we have to have all of us standing up for each other. We have to fight and oppose racism, because it attacks people in our community.”

Healthcare, too, should be something which LGBT activists care about, O’Brien said.

“There are many lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgenders who are poor, who are disabled, who are elderly,” O’Brien said. “They don’t have healthcare, so what’s going to happen to them if we don’t take care of them? If we’re a caring community, healthcare is our issue.”

Furthermore, as a woman’s rights activist, O’Brien said supporting women should be a concern of the LGBT community.

“Promoting women [in] leadership, promoting all women to go out and do whatever they want to do and to be not seen as second class so they’re paid equally at least, so they’re treated equally, that they’re not violated — those are all, to me, LGBT issues, because how can we not support our sisters?” O’Brien asked. “This movement is for all of us.”

Troublemaking today

Whether it’s the Sunrise movement, or the many women’s marches, when it comes to current activism, O’Brien is hopeful.

“I think [the Women’s March in 2017] was the largest protest that I’ve ever seen in the United States,” O’Brien said. “There were millions of women and other supporters and allies marching in the streets all over this country.”

In the face of adversity, O’Brien offered advice for future activists.

“I think the problem is a lot of young people fear it’s hopeless, [but] you don’t let them win if you give up,” O’Brien said. “In fact, you can win. I won, I beat them, the biggest churches, the biggest corporations, the people with all the power, all the respect. I was a poor kid, but I had the idea, and it’s the idea that won out.”

*Editor’s note: The California Aggie used the acronym “LGBTQ” in this article. When attributed to O’Brien, however, the acronym “LGBT” is used because, in his talk, he noted that he is “of the generation where queer was a really bad word, it was a word used against me and I’ll never forget that. What I ask young people to do is to respect that.”

Written by: Sophie Dewees — features@theaggie.org